Photography means capturing a two-dimensional perspective from a three-dimensional world. Some photographers may aim to create a realistic representation of the scenery, while others may choose a more artistic angle. Regardless of how you frame what’s in front of the lens, the first step is deciding between landscape and portrait orientations. Skipping this simple step may ruin your composition even if you follow the rules of composition and your image is technically perfect. And that’s because you overlook how the subject naturally “wants” to be framed and force it into something different. You start the photographic process with a conflict. So here is how to decide between landscape and portrait orientation in seconds and with optimal results.

Landscape Orientation

In landscape orientation, the camera is held in its default position, and photographs are wider than tall. The aspect ratio between width and height may vary, the most popular ratios being 3:2, 4:3, and 16:9. As a result, you can frame more of the environment on the left and right of the subject than above and below it or in front and behind it.

The landscape orientation is similar to how we see the world and is frequently used in nature paintings. The horizon is the reference and, thus, a powerful leading line in photography. Ensure it is straight and position it according to the rules of composition (e.g., at one-third of the frame). Most likely, the viewers will go through the photograph from one side to the other, paying less attention to depth. They expect the visual narrative to unfold around the horizon. Placing the composition’s focal point in this plane is a good idea.

However, if your composition needs depth, emphasize it by adding weight accordingly. For example, you may use the top two-thirds of the frame for distant layers, use a background in vibrant colors, or increase the distance between the subject and background.

When to Shoot in Landscape

Shoot in landscape orientation whenever the subject is rather wider than tall. A caterpillar, a mountain range, and a road going from left to right are good subjects for landscape-orientated compositions.

You may also want to use this orientation to emphasize a feature that unfolds horizontally. For example, a ballerina isn’t wider than she is tall. Still, her pose or tutu may look more gracious in landscape orientation. In this scenario, the focus is on an artistic feature rather than a physical one.

The ballerina example also illustrates another situation when you should shoot in landscape orientation: to give the impression of space. Because we mostly look at space from left to right or vice versa, we perceive space more accurately when horizontal. Therefore, consider shooting in landscape orientation when you need a lot of negative space in your photograph (e.g., a minimalist composition, a symmetry-based composition, etc.).

You may also want to use landscape orientation when the subject moves horizontally through the frame, for example, when shooting a car in motion. The wide frame is a good choice to capture the gaze of animate subjects, too. From my experience, photographs of insects taken from the insect’s eye level and shot in landscape orientation are the most effective and meaningful shots. Remember to leave more room in front of the subject than behind it.

Portrait Orientation

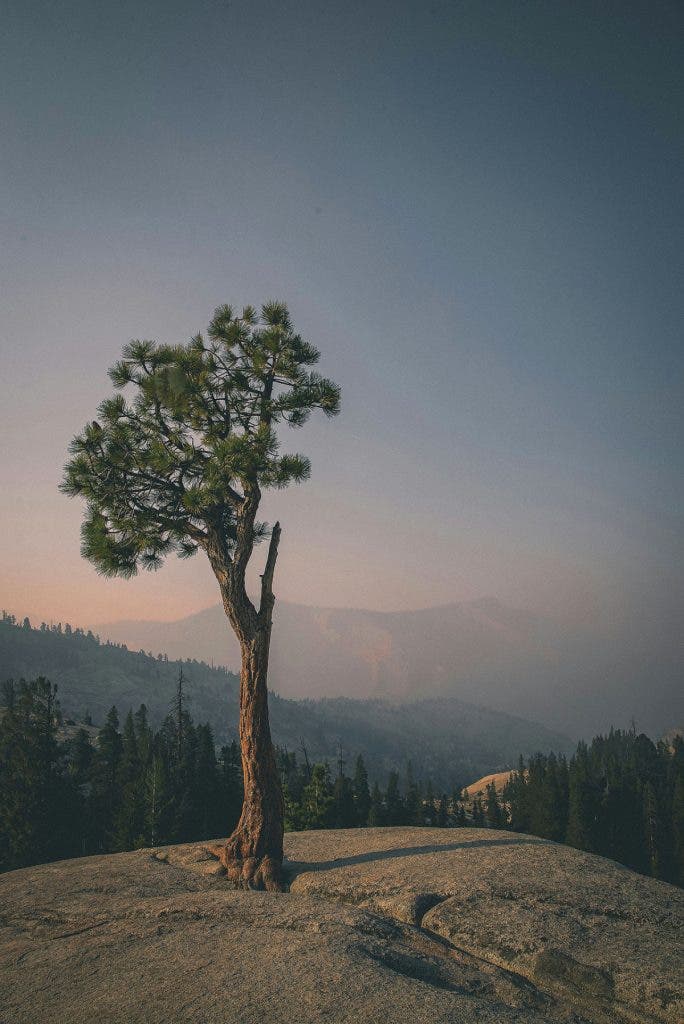

In portrait orientation, the camera is rotated at 90 degrees, and photographs are taller than they are wide. As a result, you can frame more of what’s in front and behind the subject or below and above it than what’s on either side. Trees with little foliage, giraffes, poles, and roads going from the bottom of the frame toward the top are good examples of subjects suitable for portrait orientation.

Portrait orientation refers to capturing a person facing the camera like painters do. People are tall and thin, and this framing emphasizes their natural characteristics. It also makes the subject the star of the composition, placing all the focus on it. Often, the subject fills the frame almost entirely.

However, the portrait orientation suits other photographic genres than portraiture. It emphasizes height and vertical lines, producing an artistic effect. It’s like looking at the world through a tall and narrow window. Shooting in portrait orientation leads the viewer’s gaze towards the top of the frame. Ensure there is something to be looked at there.

When to Shoot in Portrait Orientation

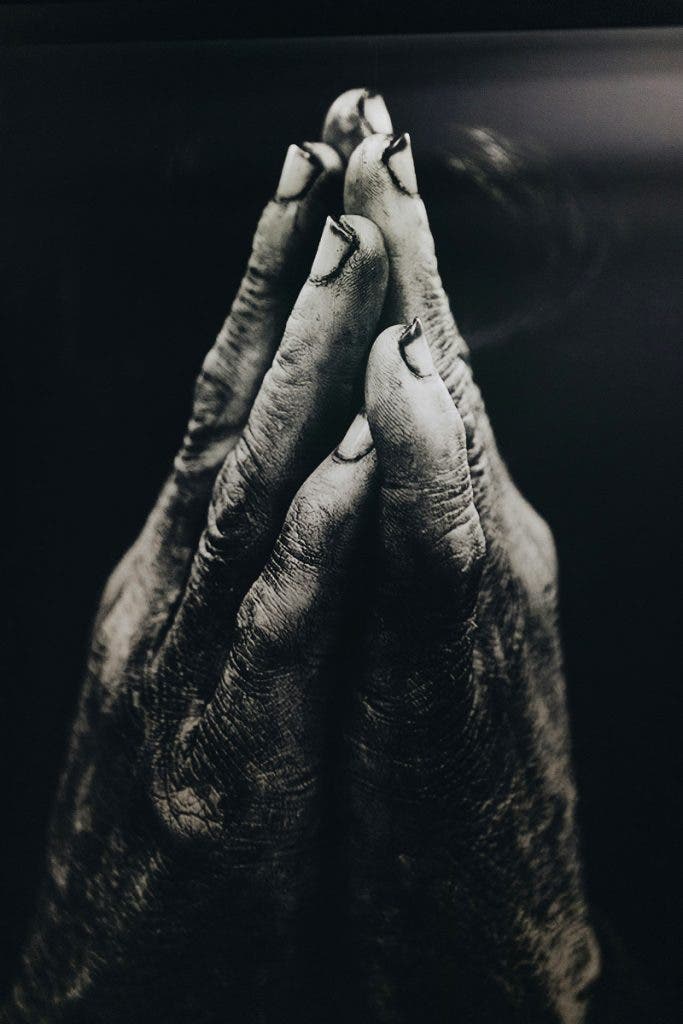

Shoot in portrait orientation when you aim to create traditional portraits of one person or when the subject’s height is a matter of interest (e.g., antennas, tall buildings, a mountain peak, etc.). You may also want to consider shooting in portrait orientation when you want to emphasize symbolic heights, such as social status, power, and authority. By positioning the camera above the subject, you diminish its importance. On the contrary, by positioning the camera below the subject, you increase its importance.

If shooting in landscape orientation gives the impression of a spacious environment, shooting in portrait orientation shrinks the space and makes objects look closer to each other. For example, people walking on a sideway will look closer to each other when shot in portrait orientation.

This means you can alter the viewer’s perception of spatial relationships by choosing one orientation over the other. The same applies to other types of relationships. For example, you can convey the close bond between two friends by using the portrait orientation. You can also enhance conceptual contrast by placing the two subjects in a landscape-oriented composition.

How to Decide between Landscape and Portrait Orientation

The best way to decide between landscape and portrait orientation is to let the subject speak to you. Consider physical characteristics (e.g., the subject is taller than wide or vice versa), motion (e.g., the subject walks from left to right, the subject looks up, etc.), space and relationships between subjects, and abstract meaning (e.g., superiority/inferiority, future/past, spirituality, etc.). You’ll see that subjects tend to let you know the framing that best suits them.

The next thing to consider is storytelling. What do you want to say with this photograph? Is it about one subject or multiple subjects, about relationships, feelings, personality traits, or events? A composition needs a rhythm or flow, which may be more relaxed (in landscape orientation) or more intense (in portrait orientation), and a narrative line. A vertical layout that allows the sky to enter the frame or a horizontal one that emphasizes the repetitiveness of a fence influences the picture’s atmosphere and message in a very subtle but decisive manner.

Besides what’s good for your artistic purposes, consider what’s better for your more practical purposes, too. For example, suppose you intend to print your photos and have a particular gallery or photo album in mind. In that case, you may consider what orientation is better for your prints and design. The photographs in online portfolios sometimes look better in landscape orientation. In contrast, photos for social media often look better in portrait orientation. Some photographers also consider the fact that smartphones and tablets, devices used for browsing through photographs, have a portrait orientation.

A few photographic genres have a say in choosing a landscape or portrait orientation. For example, professional headshots are shot in portrait orientation, and professional group shots in landscape orientation (e.g., politics, business, weddings, school photos). Many magazine editorials are shot in portrait orientation to match the page’s orientation. You’ll also notice that modern architecture landscape tends to be shot in portrait orientation while old architecture tends to be captured in landscape orientation.

Tip: Still undecided? Shoot the same scene in both landscape and portrait orientations and decide later which framing is better for your subject and artistic purpose. As a last resort, you can change the orientation in post-processing by cropping your image. However, keep in mind that cropping your image reduces the image resolution and decreases quality. Furthermore, when you take a photograph, you can change the framing, camera angle, camera-subject distance, and camera settings to produce the effect you are after. When you crop an image, you don’t have all these options. More often than not, changing the image’s orientation in post-processing will be less effective than shooting in the correct orientation.

Conclusion

It may seem of little importance whether you shoot in landscape or portrait orientation. However, you can easily recognize photos of photographers who shoot only in landscape orientation or portrait orientation. Their compositions are similar and lack something, although it may be difficult to say exactly what. Remember that a camera gives you so much artistic freedom nowadays. You should make the most out of it. Practice with different orientations, camera angles, and perspectives and observe how much the composition changes with each of them. You won’t skip choosing thoughtfully between landscape and portrait orientation after that.