Macro photography in a marine environment can be one of the most rewarding photographic activities. Don’t you just love an up-close and personal shot of small and strange creatures found in the ocean?

What actually is the classical definition of macro? It’s when the image on your sensor is actually “life” size. That means it has a one to one ratio (1:1). Anything less that 1:1 ratio would be defined as a close-up rather than macro. Close-up photography would start at magnification ratios of 1:10 and continuing down to 1:4. What this means is that the actual subject size in a 1:10 is 10 times larger than the capture image size on the sensor. Come and learn Macro underwater photography basics in this article, which was written exclusively for the Adorama Learning Center.

Macro systems are just the opposite, starting where close-up left off at the 1:4 ratio and going down to 1:1. Then there is the super-macro range, which is larger than life size. It starts with 1:1 and goes up to 10:1 magnification. Confused yet? For practical reasons, we’ll just call all types of images of small subjects as “macro.”

Glasseye snapper portrait. Because this fish was approximately 12 inches long, it was a good subject to use my Canon 50mm f/2.5 Macro lens (or if you’re using Nikon, the 60mm f/2.8G AF-S Micro) 1/50 sec at f/16. Dual Ikelite strobes, available at Adorama.

Know your subjects. Larger fish, like this pair of angelfish, make better subjects for a 50/60mm macro lens. This was a difficult shot because of low ambient light. The fish were not swimming too fast so I was able to use a slower shutter speed. 1/40 sec at f/10.

Using a 50mm lens worked better for increasing the depth of field.

Using a 50mm lens that focuses quite close, provides plenty of options. One photo shows most of the unusual shape and color of this weedy scorpionfish, the other can get a close-up face shot. These fish don’t move much so it’s easy to shoot at lower shutter speeds. 1/40th at f18.

These little twinspot gobies are fun to watch but in order to get them both in focus with a Canon 100mm f/2.8 macro lens (105mm for Nikon) I needed a lot of light using my dual strobes. My exposure was 1/60 sec at, f/ 22. By knowing a bit about behavior, I knew to look in rubble area where they have their dens. They hover over the area like little helicopters.

How can you not love this face? It’s a wobbegong shark. They generally hunt and live in sandy bottom areas. They can also get quite large—up to four feet long. 50mm lens; exposure: 1/30 second at f/16.

In order to get great fish portraits, you almost need to be a marine biologist—or at least an enthusiast. I have found that studying the likely territories for fish species and behavior certainly gave me the advantage of getting the shot that tells the story. I recommend that everyone have a series of books produced by Ned Deloach and Paul Humann. They have the definitive ID books for the Caribbean and one for the South Pacific. My favorite, however, is the Reef Fish Behavior (Florida, Caribbean, Bahamas) book. Find it here. With a little bit of study time, you can learn to recognize some fascinating opportunities to capture fish images that are amazing. Even if the book is region specific, the behavior descriptions can be used for South Pacific species that are similar. You don’t need to be a PhD; just be a photographer who is aware of your surroundings.

I love cuttlefish. They are perfect for a 50/60mm macro lens. They will perform for you like no other, flashing and changing colors. The image above was shot at a very slow shutter speed to get the ambient water background. But the cuttlefish had to be still. Exposure: 1/10 sec at f/13. The one below was shot in very dark conditions, so in order to get all the tentacles in focus I shot it at 1/50 sec at f/29.

I also recommend that you take a small area of reef and not try to swim an entire length of a football field looking for smaller animals. Spend the time and observe the movement of creatures. Many times, these animals have a routine and travel from point “A” to “B” and back with regularity. Settle down, without impacting the reef, breath slowly, and take several shots. If it’s a bit frustrating for you trying to follow a moving target, then there are a myriad of creatures that don’t move so fast. Spend time practicing on a nudibranch, a clam, or colorful tube worm. It’s a good way to test out your exposure and lighting. Yes, lighting! You’ll need plenty of that to get the depth of field that macro shots require and reduce shadows. We’ll save the specifics of this for another article.

Nudibranchs are great subject to practice on and they are so colorful. To maximize the depth field with my Canon 100mm (or 105mm Nikon) I used a shutter speed of 1/60 sec at f/32. This does, however, needed two powerful strobes to provide enough light.

With the 100mm macro lens, you can see the depth of field can be quite shallow. Note the focus is on the head of this nudibranch. The tail falls out of focus.

In the next lesson, Matt will provide you plenty of equipment options for both DSLR and compact point and shoot systems. However, I’m going to start off with a little DSLR info.

What’s the difference between a fish portrait and a macro portrait? With digital SLRs, a 50mm (Canon) and 60mm (Nikon) are the lenses of choice for fish or critters of about four inches or larger, and can be bought through the Adorama Lens dept. The drawback is that you have to be close to the subject and with fish that are skittish, it can be challenging. Photographing a colorful thorny oyster is not a problem. Gee, I wonder why? With digital camera sensors we are back to the situation of chip magnification. That 50 – 60mm macro lens is effectively a 75-90mm. See? Here’s an advantage of not having a full chip camera!

100mm macro allowed me to get a face shot of this crocodile fish (above) but also to move in and get a detail shot of his lacey eye (below).

The 100mm (Canon) and 105mm (Nikon) macro lenses won’t work for larger fish portraits, but are the mainstay of macro work with any of the small creatures. Imagine being able to get the details in the eye region of a colorful fish or a tiny blenny only an inch or two long. But wait! There’s more! Because your digital SLR is not a full chip, it makes the lens effectively a 150-160mm macro. Wow, what kind of tiny things can I photograph now? And at a distance, that skittish little creature isn’t quite so terrified of this big bubble blowing creature in neoprene.

Is there a drawback? Yes: This is underwater photography, and the distance between the lens and the subject on the longer macros mean more water in between. Crystal clear water may not be a problem but once you begin to get that “stuff” floating around, it’s bound to decrease the contrast of your image and have white specks all through it. Remember, Matt talked about ugly backscatter in a previous lesson.

Lionfish with ambient water background shot with a 50mm lens 1/30 @ f13. I certainly had to be careful with this shot because of “backscatter”. I used my dual strobes positioned so they didn’t light up the particulate.

I have seen some wonderful portrait and macro photography from digital point and shoot systems. The best advantage is that they have both zoom lens and close-up functions without changing lenses. The downside is shutter delay and the fish can be quickly gone before the capture actually happens. The good news is that shutter delay is becoming less of a problem as newer breeds of point and shoots have less delay. If you are frustrated with the delay on your system, you can pan with the subject. This means that you follow the action of the fish and fire the shutter as you follow through. It may take a little practice on land to get the hang of it. Pets make a great subject to develop your skill and who knows? You may get that favorite shot of Fido.

Photographing a stationary subject, such as this hermit crab in a shell, will make it easier if you’re using a compact digital camera that has shutter lag.

The standard flower icon on most digital P&S systems is the easiest and most versatile of all the systems. When the flower icon is pressed, the zoom elements reconfigure themselves so that the camera can focus closer. I’m always the one with a 100mm macro on my housed Canon DSLR just to notice that my photographer neighbor with the digital compact was able to capture the beautiful juvenile angelfish we were after and turn, change the icon and capture the eagle ray that was swimming just behind us.

Depth of Field

The most difficult thing to consider when photographing those small subjects is controlling depth of field. When the camera aperture is at its widest setting, the only thing in focus will be the exact focus point itself. As you magnify the subject, such as by adding diopters, the focus point becomes even more reduced. I can’t tell you how many pigmy seahorses I have photographed only to find the eye is soft! It takes lots of practice and the smallest aperture (the largest numbered f-stop). When using a small aperture, remember that this will require more light. But by stopping down the lens, it will increase the range of focus on either side of the focus point.

A tiny little blenny photographed with a 100mm lens 1/50 sec at f/22.

Normal lenses start to lose their overall image sharpness as the lens is stopped down but that is why specific macro lenses have been developed. The 100/105mm macro lenses are the key to successful macro underwater photography. It is not unheard of to have the ability of these lenses to stop down to f/32 or more!

No more than an inch long! I used a 100mm lens shot at 1/60 sec at f/25 to get as much depth of field as possible.

Compact digital cameras may not be able to stop down more than f/11. But not to fear: the chips used in many smaller sensor camera may equate the f/11 depth of field to an f/22 on a DSLR.

There are times when it will be impossible to get the entire subject in focus. The best solution is to always have the eye in focus and let the rest slowly soften away. But where do you choose the focus point when you photograph a subject that doesn’t have an eye—such as a clam? Well, this allows the creative forces in you to work. Experiment, look at the LCD and learn what is most pleasing to you!

This small flathead was trying to hide in the sand but his “Frank Sinatra” eyes were a dead giveaway. 100mm lens shot at 1/60 sec at f/22.

I know, you have one serious question to ask. “I can’t see the subject clear enough to find the focus point!” That’s why they do have prescription masks for us old people! I’ve even discovered that by having one contact lens for close work works really well. I can read/see the back of my LCD and find the subject. What a concept!

There is so much to cover in this area of underwater photography that we will continue with more lessons addressing lighting, composition, and super macro. The bottom line to macro photography is to have fun and learn more about some of the amazing small creatures in the underwater world.

Remember: You can purchase all of your underwater cameras and related equipment at the Adorama Underwater Photography Gear shop.

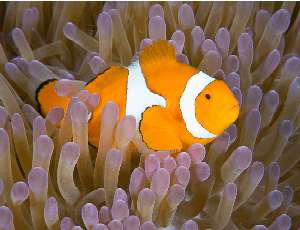

Clownfish can be somewhat difficult to photograph because they move around the anemone so quickly. However, a little patience and you may find one that settles down a bit to get an image. 100mm lens.