When Kodak unveiled Ektar 100 in the 35mm size nearly two years ago they proudly proclaimed it to be The World’s Finest Grain Color Negative Film.

Kodak also clearly implied that Ektar 100 benefitted from company’s ongoing research on motion picture film, perhaps the most active film-use category in the digital era. Kodak also endowed the new film with their latest emulsion technology, including such impressive sounding stuff as Micro-Structure Optimized T-GRAIN and Advanced Cubic Emulsions, and Optimized Emulsion Spectral Sensitivity and Image Modifier Chemistry for ultra-vivid color.

In general, the 35mm version received such rave reviews in the press and among film testers, I can well believe Kodak’s claim that they introduced Ektar 100 in 120 roll-film literally by popular demand.

While Ektar 100 is a broad-spectrum film recommended for such applications as nature, travel, outdoor, fashion, and product photography, Kodak does not consider it optimal for portraiture, primarily due to its intense color saturation. They recommend Kodak Professional Portra films for “consistently natural reproduction of the full range of skin tones.”

However, many photographers are attracted to Ektar 100’s other sterling virtues, including high sharpness, extremely fine grain, and medium contrast will undoubtedly include people in their pictures. To address this, I conducted a controlled experiment to assess its skin tone reproduction.

First, let’s do some Silver Halide peeping

Anyone needing full technical data on Kodak Ektar 100 in 35mm and 120 sizes can download Kodak publication E-4046 on the Kodak Website or by googling Kodak Ektar 100. Some fascinating facts gleaned from this document: The acetate base for Ektar 100 in 120 is thinner than the 35mm stock—0.10mm as opposed 0.13mm—due in part to the paper backing.

Also, based on the Print Grain Index, the latest method for comparing prints made with diffuse light sources, an 8×10 made from a full-frame 120 neg shot on Ektar 100 film will have no visible grain, a 16×20 examined at normal viewing distance will have virtually no grain, and a 16×20 print viewed at a very close distance will have just noticeable grain.

Not surprisingly, this is much better, print size for prints size, than 35mm because of the magnification required to make a 16×20, which is 17.6X with 35mm, but only 8.8X with medium format. To check this out I conducted a seat-of-the-pants side-by-side grain comparison of Ektar 100 and Portra 160NC.

The royal scan

Another interesting tidbit: While Ektar 100 is described as “easy to scan,” no standards exist to define thee spectral response of various scanners—each manufacturer’s scanner has its own spectral output, and the results also depend on the matrices the scanner uses to output information to CRT monitors, etc.

To address this knotty problem, I had test prints from the original negatives made using the traditional photographic enlargement method on Kodak Supra Paper by LTI New York, and also 2000ppi scans of 145MB each made by Richard Sjolund of Wilderness Studio LLC of Solon Iowa on an Imacon Precision II scanner,, which is reputed to provide image quality comparable to a drum scanner. Since well over 90% of prints shot on Ektar 100 will be made from scans these days, the comparison is relevant an illuminating.

Note: Our conclusions on image quality are based on a close examination of both types of images, but the color rendition comments are based on the photographic prints.

Test parameters

To get the very best image quality possible in my practical field test, I shot 10 test rolls of Ektar 100 using a Hasselblad 500C/W camera fitted with the standard 80mm f/2.8 Carl Zeiss Planar lens. The camera was checked and calibrated to assure accurate lens-to-film-plane alignment and also precise correspondence between the focusing screen and film plane.

To minimize variables encountered with paper-backed roll film, I shot several frames of each test subject, at moderate apertures in the f/8 to f/11 range whenever possible, and picked the sharpest image. I pre-fired the mirror before making the exposure to minimize camera shake and picked the sharpest image from each set. The only times I didn’t pre-fire the mirror was when I shot at 1/250 sec.

The camera was mounted on a sturdy Davis & Sanford Carbonlite Transporter tripod with 3-way head and the center post was raised as little as possible for maximum stability. Incident meter readings were made with a Sekonic L-558 meter of known accuracy, and given the wide latitude of color negative, films I bracketed exposures at 1-stop intervals to get a handle on over- and underexposure latitude and shadow detail rendition.

Test photos

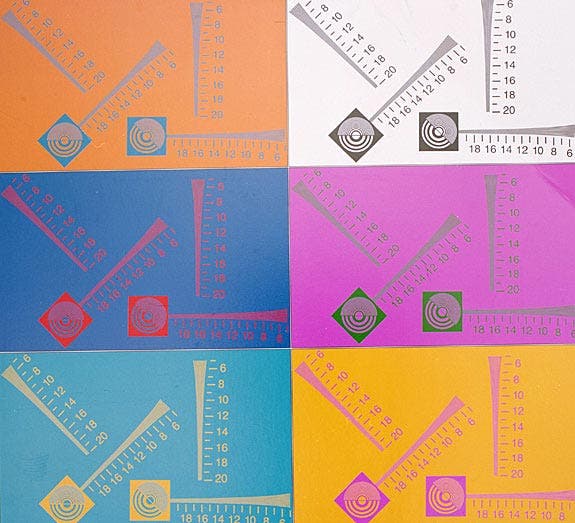

Test target: I shot a resolution test target placed parallel to the film plane at a distance of approximately 6-1/2 feet to assess overall image quality and fine detail rendition. The target includes subtractive color arrays that can theoretically provide figures for system resolution in various colors, but I did not attempt to quantify the results since it was evident that the resolution capability of the film itself far exceeded that of the lens, which resolves about 64 line-pairs per millimeter in the center of the field and about 40-50 line pairs per millimeter in the corners at the optimum aperture of f/8 based on previous tests shooting USAF test targets on Kodak Tech Pan.

Test target at almost full frame

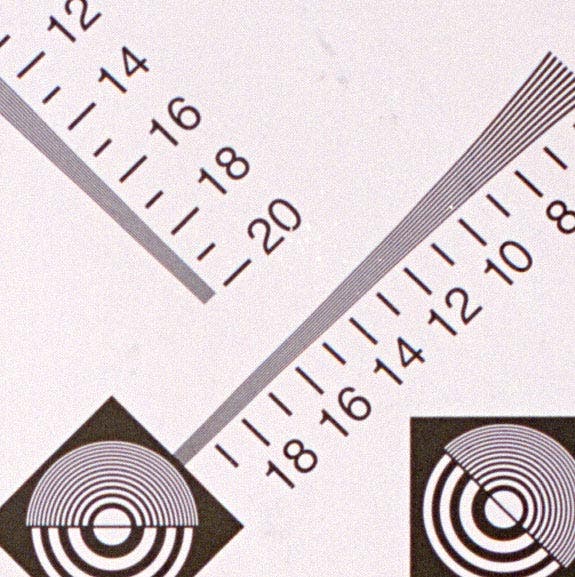

100% blow-up of detail area near corner of frame shows outstanding resolution.

Shirley: As insiders know, a Shirley is a portrait of an attractive young woman holding a MacBeth Color Checker in natural daylight that’s used to assess a film’s color reproduction characteristics. Our Shirley was shot on a cloudy-bright day (perhaps a tad cooler than the optimum 5500K), but it nevertheless gives an accurate representation of the film’s color characteristics. Also, when the chart was printed to correspond as closely as possible with the actual Color Checker, it provided an accurate picture of the film’s inherent skin tone rendition.

Meet Shirley, our model, holding a GretagMacbeth Color Checker, which showed remarkable color accuracy in our prints (screen color accuracy may vary—read our text for the most accurate description.)

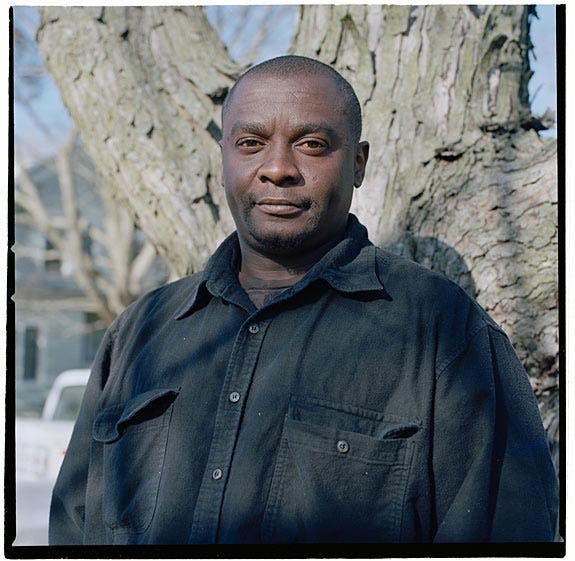

Mike: Mike is an African-American with medium-brown skin, and he’s wearing a black shirt. I shot his portrait in late afternoon sunshine primarily to assess shadow detail, but the picture also provides some information on exposure latitude and the film’s ability to differentiate subtle skin tones.

Hi, Mike: Ektar 100 showed remarkable shadow detail in this shot.

Victorian house: I photographed lavish Queen Anne style mansion festooned with exuberant detail. I shot it to provide information on the exact type of subject for which Ektar 100 is optimized. I also enlarged a central section of this picture to the equivalent of a 16×20 print for our grain comparison, which incidentally is presented verbally rather than pictorially, since the limits of web resolution and variable monitor color rendering would not do it justice.

Queen Anne would be proud: Detailed subject at full frame…

…and a 100% blow-up shows near large-format quality.

Still life: This assemblage of fruits, veggies, music, and a metronome on a lacy background was configured to provide information on natural color rendition, highlight and shadow detail, and overall detail rendition.

Observations and conclusions

Grain: Unquestionably, Kodak is justified in claiming that Kodak Ektar 100 in 120 is an extraordinarily fine-grained color negative film. To see any grain at all in our 16×20-equivalent enlargement I had to view the print from about 6 inches, and even then the grain pattern is amazingly fine and uniform!

The Kodak Portra 160NC I used for comparison (not shown) is certainly no slouch in the grain department, but under similar viewing conditions it’s grainier and the grain pattern looks a bit blotchy. If you’re wondering whether Ektar 100 is finer grained than Ektachrome E100G, based on the ‘chromes in my files I’d say definitely yes.

Color rendition: Based on the GretagMacBeth Color Checker results, Ektar 100 in 120 definitely delivers very high color saturation for a color negative film, although not as high as, say Fuji Velvia. It seems to be biased toward the red and to be less saturated in the greens, which sometimes tend toward the olive. Yellows are generally accurate but on the vivid side, occasionally tending to skew toward the red. Having thus nit-picked I’d have to say that the overall color rendition is pleasingly vibrant, and I was very impressed with the film’s ability to deliver attractive, well differentiated skin tones with both the Caucasian and African-American subjects.

The skin tones in Mike’s portrait are outstanding and so is the shadow detail in areas of his black shirt that are at least two stops underexposed. The female model in the Shirley has surprisingly well-differentiated, natural looking skin tones. Though portrait specialists may find it a bit too contrasty and a tad on the ruddy side compared to the Portra films that are optimized for portraiture, Ektar 100 shooters can expect satisfying results when they include people in their pictures.

Detail rendition: As expected, Ektar 100 is capable of delivering such amazing sharpness you had better use all the technical controls at your disposal if you expect to get the most out of it. Examine the scale of the metronome or the detail in the lace in the center of the right-hand side of the still life image, and the blinds in the window to the right and just above the porch turret on the Victorian House picture to see what I mean. This approaches large format performance in terms of detail rendition—very impressive indeed.

Other observations: The color patches on the MacBeth Color Checker give a good picture of Ektar 100s vivid but commendably accurate color rendition, a consequence of its intense color saturation. Like many films it stubs its toe on the tricky Blue Flower patch the model’s fingers point to. It’s worth noting that all films with very high color saturation invariably provide less differentiation within a given hue than films with low or moderate color saturation.

The price you pay for reproducing a strawberry or a rose that seems to pop off the page is that the subtle variations in red are attenuated or lost entirely. With Ektar 100, this is especially noticeable in the reds, the hues with the highest color saturation As for exposure latitude in practical terms, with most subjects it ranges from 4-5 stoops over to 2 stops under, impressive even by color negative standards. If you doubt this, take a close look at the still life that shows discernible detail in the cello tailpieces (2-3 stops under) and a bit of detail even in the lace curtains in the upper-left-hand corner (5 stops over).

Speaking of detail, it is possible to count lines down to about number 16 on the diminishing linear array on the resolution test target image, but the inability to resolve even finer detail is due to the limitations of the lens, not the film—if you doubt this, check out the MTF chart in the Kodak Tech Data sheet.

Conclusion

Ektar 100 in 120 takes top honors in terms of overall flexibility, ultra-fine grain, and its ability to capture superb detail and deliver pleasing but vibrant color rendition over a wide variety of shooting conditions. If a film of moderate ISO 100 speed works for your particular application this is simply the best color negative film currently available for medium-format shooters. I sure hope Kodak considers bringing it out in 220, also by popular demand.

Many thanks to LTI New York 34 East 30th St. New York, NY 10016 for making the prints used for evaluation in this article. LTI is a full service photography lab with focused is on providing the high quality photographic services to a clientele of Professional and Fine Art photographers. Services offered include film processing, optical color and black & white printing, scanning, digital retouching, digital c-prints and archival pigment (inkjet) printing.