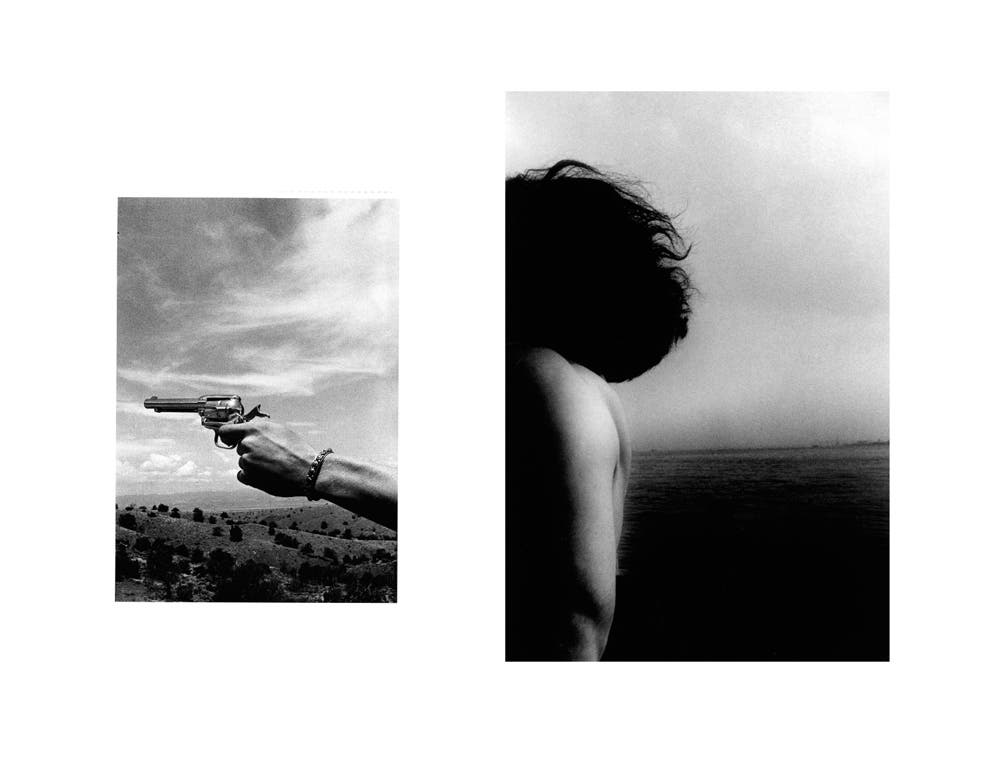

To say that Ralph Gibson is an internationally acclaimed photographic artist is something of an understatement. He is a consummate original that has done nothing less than forge his personal perceptions and way of seeing the world into a coherent aesthetic that transcends mere “style.” His work is utterly unique and instantly recognizable, with strong graphic elements and provocative juxtapositions. But paradoxically the man behind these images disappears, leaving only the subject—enigmatic, compelling, and, in a sense, eternal. Gibson’s images are transcendent precisely because they do not “tell a story” and are not “about” anything but themselves. They convey the pure “it-ness,” the radiance of being, of whatever is in front of his camera.

To say that Ralph Gibson is an internationally acclaimed photographic artist is something of an understatement. He is a consummate original that has done nothing less than forge his personal perceptions and way of seeing the world into a coherent aesthetic that transcends mere “style.” His work is utterly unique and instantly recognizable, with strong graphic elements and provocative juxtapositions. But paradoxically the man behind these images disappears, leaving only the subject—enigmatic, compelling, and, in a sense, eternal. Gibson’s images are transcendent precisely because they do not “tell a story” and are not “about” anything but themselves. They convey the pure “it-ness,” the radiance of being, of whatever is in front of his camera.

Gibson’s career as a photographer really began when he enlisted in the Navy in 1956 and became a Photographer’s Mate. This was a relatively new position created by Edward Steichen who had set up the Navy’s photographic program during World War II. His instructors in Pensacola had studied with Minor White, and he was given a very fine and thorough education in the fundamentals of photography. “By the time I left the Navy as a PH-2, I was adept at mixing E-1 chemicals and I knew the Zone System backwards,” he recalls with a smile. On the basis of his technical skills, Gibson was invited to become an assistant to Dorothea Lange, the renowned documentary photojournalist best known for her iconic images of the Great Depression. Eight years later he was in New York working with Robert Frank, another brilliant documentary photographer, who was Swiss trained but preferred to capture the raw texture of reality rather than achieving technical perfection. The big lesson he learned working with both these masters: that being original is the most important thing. As Gibson himself puts it, “I’ve always wanted to announce my own personal themes rather than perform variations on previously established themes.”

Gibson has had a lifelong fascination with books and bookmaking, a passion that only increased when his landmark book The Somnambulist was published in 1970. In 1967 he moved to New York and in 1969 founded Lustrum Press to retain control over the reproduction of his work. To date he has produced over 40 volumes illustrated with his images, including State of the Axe (Yale Press, 2008) and Nude (Taschen, 2009). A list of his gallery and museum exhibitions goes on for 3 pages, and his work is held in numerous prestigious collections including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Whitney Museum of American Art, International Center of Photography, Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art in Kansas, Museum Ludwig in Cologne, Germany, and the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. Among his scores of coveted awards: a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1985, a Lucie Award for lifetime achievement in Fine Arts in 2007, and an appointment as Commandeur de L’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, by the French government in 2005. In 2016 Ralph Gibson was named Photographer of the Year at the Palm Springs Art Fair and presented an all-new series of photographs entitled Vertical Horizon at the opening of the Galerie Thierry Bigaignon, a color departure from the black-and-white images for which he is celebrated.

Gibson bought his first Leica in 1961, an M2 with a 50mm f/2 Summicron lens, and immediately realized that this camera and its subsequent models was destined to be his instrument for the rest of his life. He recalls saying to himself, “This camera is capable of doing anything I am capable of asking it to do,” and he has had little reason to change his mind since. When Leica approached him to endorse the Monochrom, a high-performance black-and-white-only digital Leica M, he had spent 55 years in the darkroom and the analog process was losing its appeal. The first image he made with the “Mono” was the bicycle shown here, and he was delighted with it. “This convinced me that digital not only reflected my vision, but perhaps even enhanced it,” he astutely observes. “Imagine the great fortune to be able to reinvent yourself about the time you turn 75!” The only thing he doesn’t like about digital: “I cannot seem to set the camera down…there are images everywhere…”

The publication of The Somnambulist established Gibson’s worldwide reputation as a leading art photographer, which he describes tongue in cheek as a “minuscule profession.” However, it also freed him up to pursue personal projects rather than having to prioritize the needs of clients. He certainly didn’t want anyone telling him what to shoot, and then pass judgment on the results. As he succinctly puts it, “I wanted to be autonomous, to take all the credit and all the blame.” Fortunately, he had the sheer talent and entrepreneurial savvy to be able to flourish and support himself as a photographic artist for well over 4 decades. However, over the past few years, he’s been shooting some commercial fashion, which he laughingly refers to as “my hobby.” Not surprisingly, his fashion images are outstanding because they’re also works of art that are several cuts above the typical fashion fare. “I now find shooting fashion a real change in rhythm,” he says enthusiastically, “and I welcome the hoopla of the production team, the beautiful clothes, and the models—when they are good-:)”

What makes all of Ralph Gibson’s images stand out is really the mindset behind them, the way he perceives photography. “I feel that the real subject of my photographs is my perceptual act, in and of itself,” he observes, and this is what explains the absence of an “event” in most of his images. “I want to make photographs of very humble subject matter,” he continues. “I’m not waiting for a bullet to enter the victim’s brain and then call it my photograph,” perhaps an unconscious reference to Eddie Adams’ searing Vietnam War image of a Viet Cong officer being executed with a pistol to his head.

Throughout his long career, Gibson has made countless photographs for many different reasons, but his overall concern has always been to charge each image with as much content as possible. That’s one reason he eschewed commercial work for so long, which he saw as “ephemeral in nature and intent.” He feels that the names of various art movements to describe what an artist does can be useful, but are inherently limiting, and that narrative photographic images hold little interest for him. “Having started out as a documentary photographer remains useful only in that it enables me to access the camera handling skills most often used in street or documentary photography,” he says emphatically, “but that’s not what I do. Samuel Goldwyn famously said, ‘If you have a message, send a telegram!’ I have no message. For me, the most attractive thing about photography is that what one is seeing is not necessarily in the photograph—that’s the transcendent quality that attracts me in the first place.”

While Ralph Gibson is well aware that one can never acquire an artist’s transcendent vision simply by taking a course, or attending a workshop or lecture. However, he is firm believer in the value of photographic education. And he is committed to giving something back that will be of use to photographic enthusiasts and emerging artists and professionals going forward. That, and his lifelong Leica connection, is why he’s held a series of well-attended workshops at the famed Leica Akademie.

If this article inspires you, please check out Gibson’s latest Leica Akademie workshops below:

July 14th-16th – Book Making Workshop – San Francisco – Click here for more details

August 10th- 13th – Photographing the Nude – New York Click here for more details

To see and hear Ralph Gibson’s entire body of work in depth including his amazing movies, and his compelling musical and multimedia creations, please go to his website.