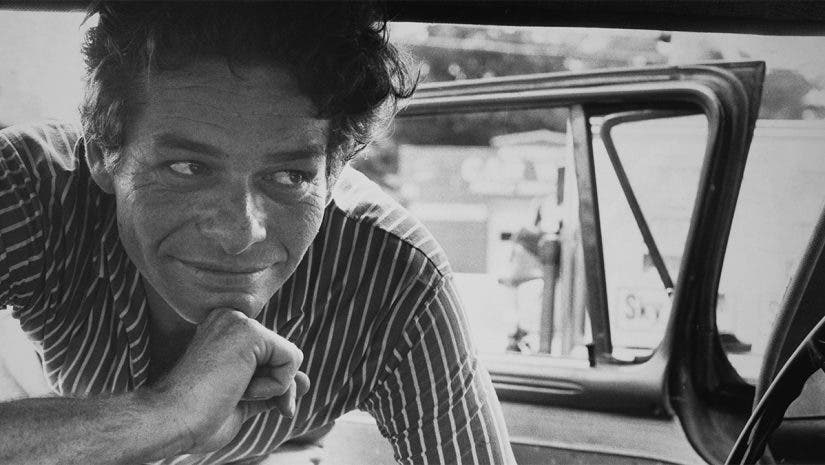

Garry Winogrand was a principal photographer of his generation known for his extremely prolific output of loose yet sophisticated frames of candid daily life. Notoriously matter of fact about photography, Winogrand voraciously explored its purely descriptive qualities, famously uttering “I photograph to see what the world looks like in photographs.” Winogrand’s physical, inspired approach depicted the streets with an unprecedented, tenacious energy that resulted in an unflinching, at times controversial, documentation of modern life in the mid-twentieth century.

Choosing Art Over Commerce

Winogrand was born in the Bronx, New York City, in 1928 to working class parents who emigrated from Budapest and Warsaw. After graduating high school, he enlisted in the army but was honorably discharged soon after due to an ulcer. In 1947, he returned to New York and began studying painting at Columbia University under the GI Bill. However, within weeks, he became obsessed with the institution’s darkroom. Open to students 24/7, its constant availability was just his speed. And thus began Winogrand’s lifelong quest of looking at life through the lens.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Winogrand worked as a freelance photojournalist and advertising photographer. These were the only professional paths available to photographers at that time. But photographing for a reason other than his own personal compulsion soon felt disingenuous. So he began carving out a life as an artist, unchartered though it was. Armed with a 35mm Leica M4 rangefinder and a 28mm lens, Winogrand preceded to create a voluminous archive of complex photographs that would help usher in photography as a bona fide fine art.

A Relentless Life Pursuit

In 1955, Winogrand had a photograph in the hugely popular The Family of Man exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. However, his break-out exhibition was Five Unrelated Photographers at MoMA in 1963. This exhibition also included photographers Minor White, George Krause, Jerome Liebling, and Ken Heyman. Three years later, MoMA curator John Szarkowski, who would become a lifelong champion of Winogrand, mounted New Documents, a show comprising his photographs, Lee Friedlander’s, and Diane Arbus’. The exhibition reset the discourse on documentary photography toward more personal depictions of the social landscape. It also made him one of the most famous street photographers of his time.

Career Highlights

Winogrand preceded to publish several books, including Women Are Beautiful, rather provocative photographs of women he encountered on the street; Public Relations, photographs of demonstrations, parties, and political events during the turbulence of the 1960s and 19760s; The Animals, photographs about human and animal interaction made at the zoo; and after his move out West, Stock Photographs: The Fort Worth Fat Stock Show and Rodeo, photographs of events at the cattle industry exposition. He taught at the School of Visual Arts, Cooper Union, the Art Institute of Chicago, University of Texas-Austin, and elsewhere, and obtained three Guggenheim Fellowships, as well as a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship.

Winogrand relentlessly pursued his craft until his death from cancer in 1984, leaving behind around 2,500 undeveloped rolls of film and about 300,000 unedited images. In 1988, MoMA mounted a posthumous retrospective exhibition that included an edited selection of this output by his colleagues and close friends Thomas Roma and Tod Papageorge. Years since, traveling retrospectives were organized by San Francisco MoMA and the National Gallery of Art, which toured internationally. In 2019, the Brooklyn Museum mounted an exhibition of his color work culled from more than 45,000 color slides made in the 1950s and late 1960s. Posthumous publications include Figments From a Real World and Winogrand Color. In 2018, Sasha Waters Freyer directed the documentary film Garry Winogrand: All Things Are Photographable, which screened in theaters and on PBS’s American Masters series.

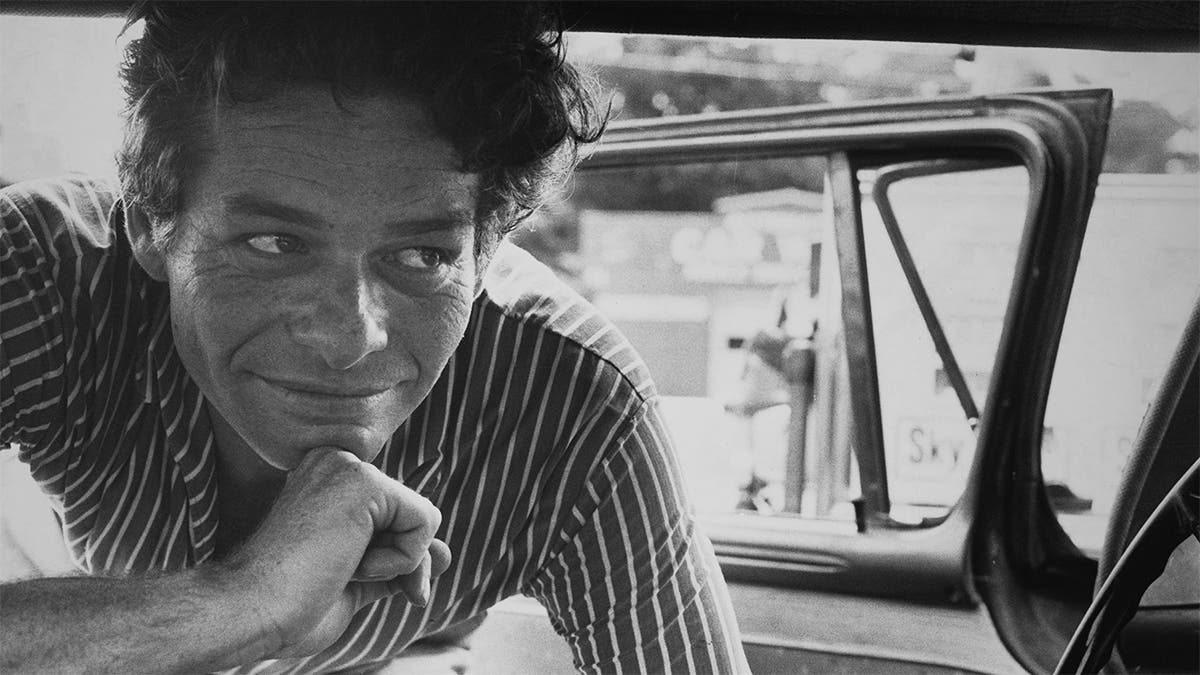

Working the Frame

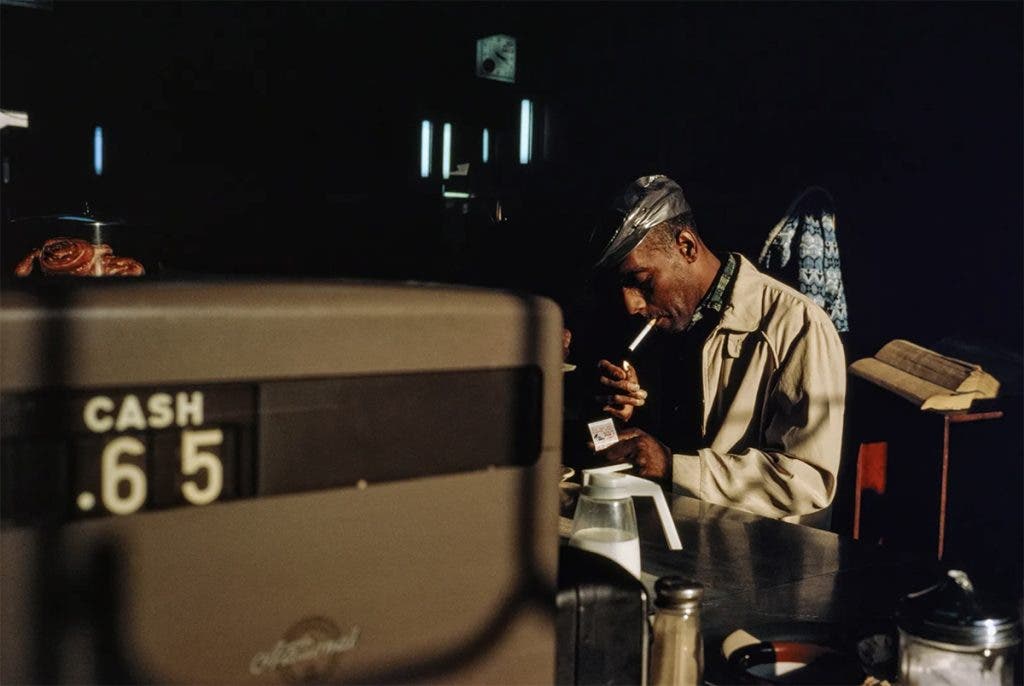

This is one of Winogrand’s most famous images and certainly one of my favorites. This photo is More than just a spot-on documentation of the 1960s. It is a quintessential Winogrand shot that belies just how much work it takes to make a picture wherein all the elements in the frame sing. In the documentary Garry Winogrand: All Things Are Photographable, he talks about being inspired by what was unveiling before his eyes when he made this picture and the necessity of photographing through that as the form and the content came into perfect alignment.

The Encompassing Wide Angle

Winogrand was terrified of flying. In 1959, his mentor, Dan Weiner, died in a plane crash, and it left him feeling superstitious. To shake off his nerves while waiting to board, he often photographed at airports. There, he utilized the breadth of his 28mm lens to make a sweeping vista of interior daily life. Part of Winogrand’s talent was harnessing the chaos of reality and the copious visual elements that the wide angle lens afforded him. Here, we have sweeping arcs, grids, shapes, lines, and a cacophony of anonymous people lit by gigantic windows just doing their thing in a highly gratifying composition.

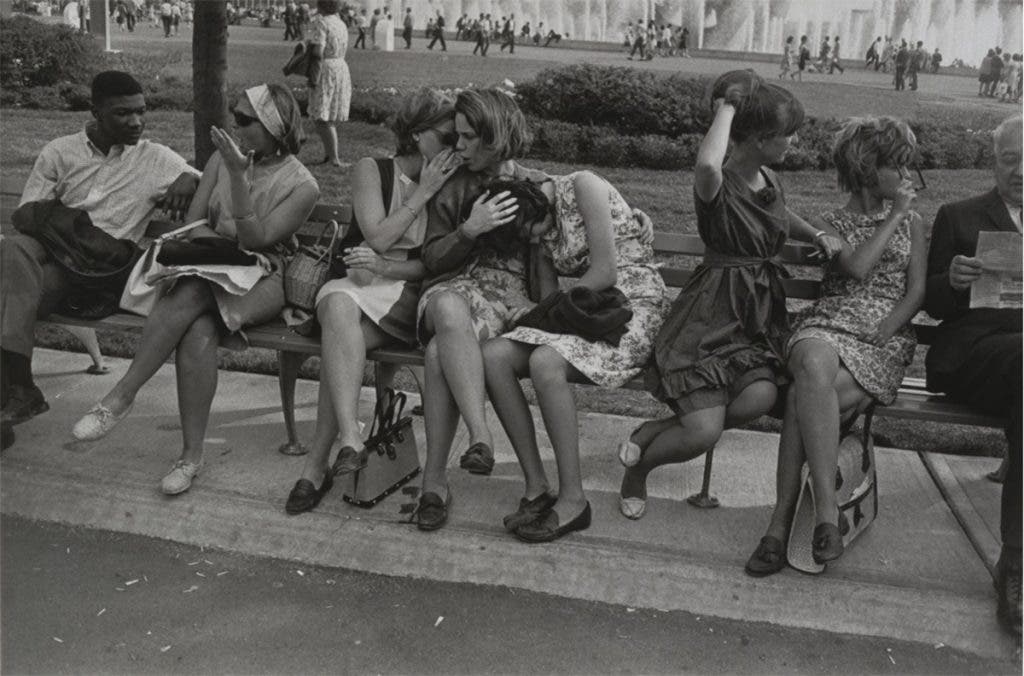

Unflinching Social Commentary

There’s a lot to take in here—just as Winogrand liked it. Not only has he succeeded in contending with various visual elements, the content itself is a mix of the extraordinary and the ordinary. What appears, at quick glance, like an everyday congregation of people in anticipation of something (a bus arrival? a crosswalk cleared of traffic? the end of a smoke break?) also happens to take place outside an event for veterans, one of whom has suffered an atrocity that no one seems struck by except the individual himself. What to make of it? Winogrand doesn’t have the answers; he just poses the questions.

Creating Photographic Opportunities

Winogrand’s first publication was also one of his first bodies of work, The Animals. He made it while he was on dad duty. Those are his children, Ethan and Laurie, hanging upside down. Major props for any artist who can somehow make work while parenting. Winogrand loved his children deeply—as well as children in general—so the zoo was the perfect place to entertain his kids and, at the same time, quench his voracious appetite for shedding light on who we are as living beings—animals and humans alike.

Color Connections

Until rather recently, when Winogrand’s color slides finally saw the light of day, Winogrand was largely known for his black and white images. Winogrand was deeply attuned to monochromatic imagery, both artistically and practically speaking. But he often photographed with two cameras, one loaded with color, the other with black-and-white, and I thank the street goddesses for that. The dots that he connects through chromatic relationships are highly satisfying as a viewer and only enhance the richness of his complex compositions and perspectives.

Instinctively and Tirelessly Searching

Some regard Winogrand as the first “digital” photographer because he photographed so frequently and with so much abandon. He was often at least two years behind in developing and printing, and toward the end, maybe even lost the impulse to develop and print at all. To him, it wasn’t about the pictures (noun). It was about making pictures (verb). He was constantly trying to make sense of the world, a hopeful pessimist who roamed the streets in search of answers. I don’t know that he ever found any, but he never lost sight of photography’s ability to at least show, in visually descriptive terms, what living looks like.

Winogrand left behind very little written record of his thoughts on photography—no letters, no diaries, no journals. But there are a few great interviews with him, which seem to reveal most of all the mystery photography possessed in his mind. Unable to define it as anything other than light on a surface, its power gripped him until the very end. “Whatever it is,” he said, “I can’t seem to do enough of it.”