I fly a lot. On those days, when the weather and the wind dictate that planes incoming to New York must fly over that narrow band of land that is Manhattan, I always look. It’s captivating. The city jabs its graphical way skyward — concrete upon concrete — demanding attention and wonder.

For many years, the Trade Centers strode over it all — twin exclamation points at the southern tip of the magnificent mess that is New York. As a photographer, it was hard not be in love with them. Include them in a photo (and you could from just about anywhere in the metropolis) and you had instantaneous location. You offered information and beauty to the viewer of your photo in the simplest of clicks. The towers were in too many movies to count.

Documenting the Towers

I moved to New York in the summer of 1976. The twin towers were relatively new then. They were glistening, shiny slivers presiding over what was then a city that was filthy, crime-ridden, and desperate. Working as a copyboy at the New York Daily News, I was running copy, doing errands, and getting coffee for editors. I would take subway rides to meeting points to collect sturdy bags stuffed with film cassettes from photographers out in the world riding in radio cars, hunting the urban jungle for the stuff of page-one news.

One such page one was George Willig, the human fly, who devised his own clamps and rigging to climb the outside of the South Tower all the way to the top. At first, the city charged and arrested him. Although, he became such a folk hero that Mayor Abe Beame ended up fining him $1.10 — a penny for every story he climbed. Those skyscrapers were the visual postcard signature of New York, and became part of the legend and fabric of the city.

“They were so immense and durable. I thought those towers, like the city, would always be there.”

My personal history with the towers began in earnest in 1977 when I climbed the antenna on the North Tower. I ascended with a maintenance crew in what was to become the first of many urban climbs I have made as a photographer. I remember being up on that tower, feeling it sway in the wind, and looking out at the never-ending city. They were so immense and durable. I thought those towers, like the city, would always be there.

And Then They Were Gone

The Trade Centers were the graphic anchors for many stories and photos over the long visual history of the city. And then they were gone. The planes hit the buildings, which took over ten years to build, and they both crumbled in less than two hours. The massive, suffocating dust cloud that enveloped lower Manhattan muffled and broke the beating heart of a city that never stops, never sleeps.

“The scar of 9/11 in NYC is a wound that will not heal. It is high, wide, deep, and painful. Also, it’s ennobling. It is New York at its darkest hour, and its finest.”

The scar of 9/11 in NYC is a wound that will not heal. It is high, wide, deep, and painful. Also, it’s ennobling. It is New York at its darkest hour, and its finest. Like a badly pummeled prize fighter, down for the count, the city pushed itself up off the bloody canvas and fought back with all its strength. An army of rescuers, from all walks of life, rushed to where the towers stood.

Like many at that time, I searched desperately for something to do. How to contribute? I’m not a cop, an iron worker, or a firefighter. Many photographers made their way to the pit, recording the immediacy of the destruction in powerful, memorable images. No need for another one. What to do? How might it be possible to photographically honor the sacrifices being made, and record in pictures the faces, lives, and stories of those who rose up in heroic fashion, saving the wounded and injured, and in doing so, saving all of us as well? How could that be done in a way that was distinctive, and respectful?

Documenting the Heroes

I had one experience working with the world’s only giant Polaroid camera which, at 9/11 time, happened to live on the lower east side of Manhattan. The personal invention of Dr. Land, who originated the Polaroid process, it was a behemoth of a camera. It was the size of a one car garage, with two technicians inside of it working the machinery of this unique picture instrument. It was such a singular camera, a one-off, that the National Geographic assigned me to do a small story about it in 2000, which is how I came to know of its existence.

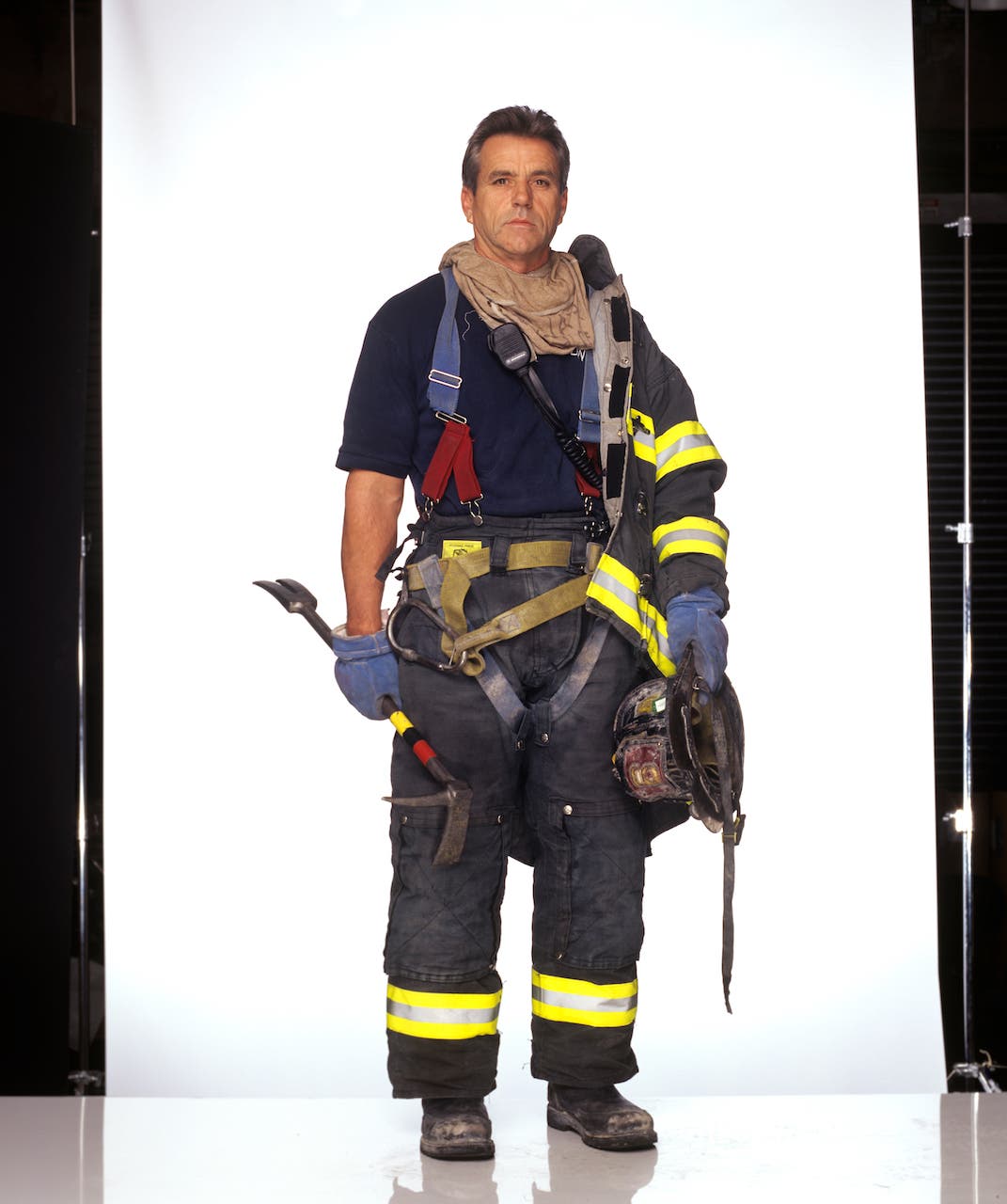

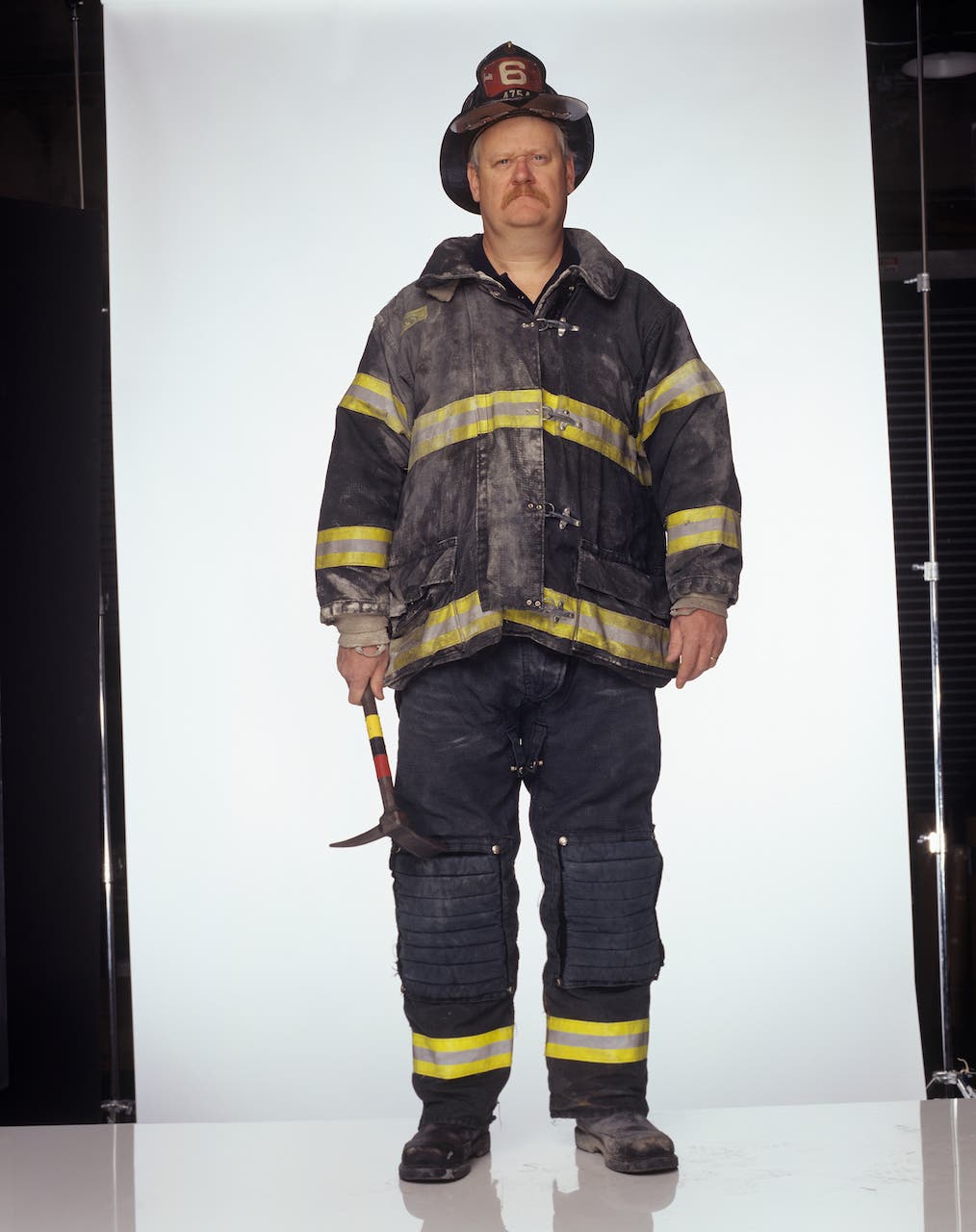

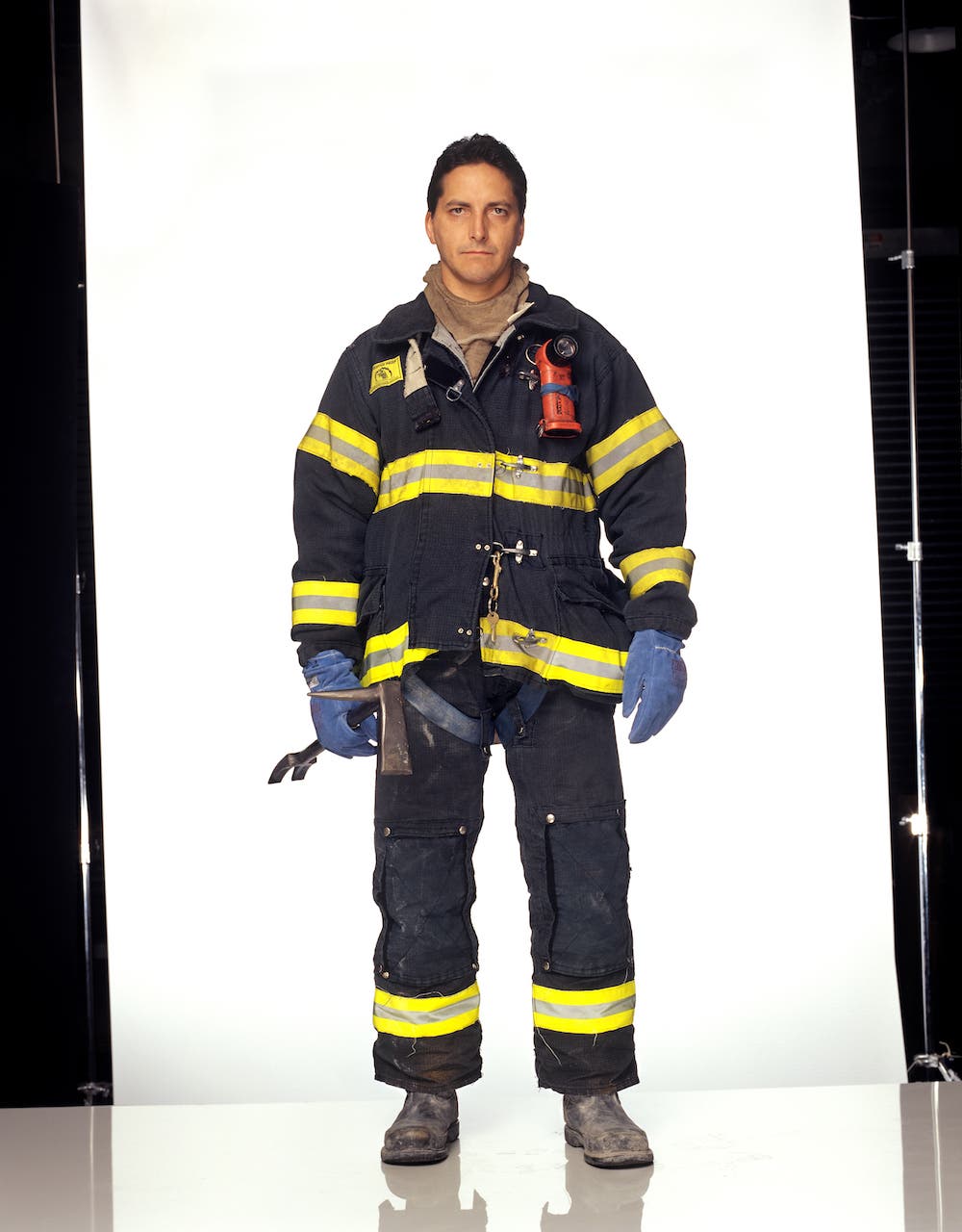

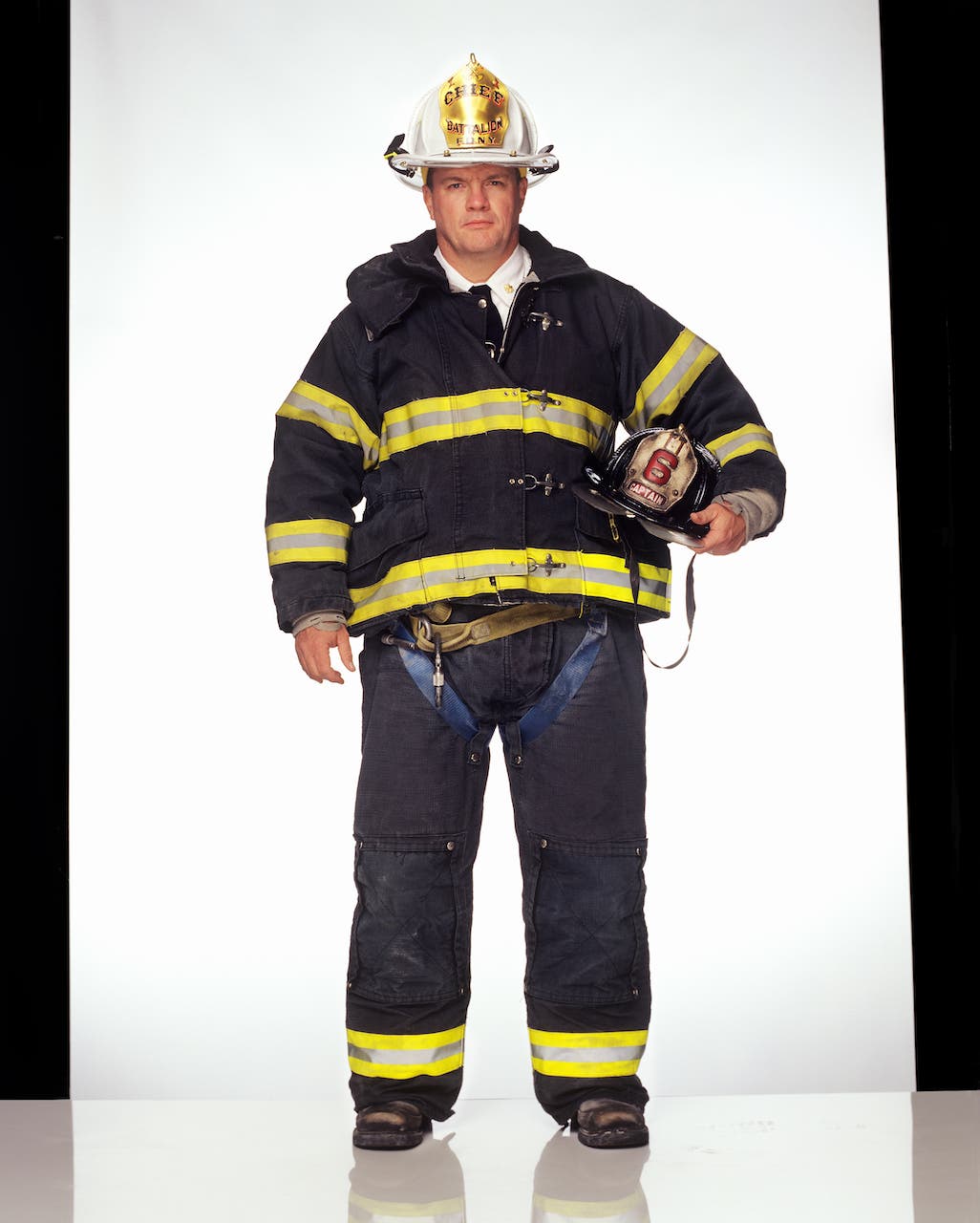

It’s an odd combination of modern camera technology and old-timey portraiture practices. The subject must stand very still for their portrait, while the camera is prepped and focused. The studio lights need to be doused. The cap is pulled off the massive lens that serves as the portal to the interior chamber. With a single pop of a powerful flash system, the subject is recorded, life-size. Ultimately, during the three-week period we operated at the Polaroid studio on East 2nd Street off the Bowery, 272 people stood in front of that lens.

For the viewer, standing in front of one of these life-sized Polaroids is akin to meeting the person in the picture. It’s an emotional encounter. They gaze back at you. And, given the fact that these portraits were all shot within a month of 9/11, those faces spoke a powerful, emotional truth. You cannot look away from the hurt, the stress, the exhaustion, the bravery, and the pride.

The Faces of Ground Zero

These life-sized Polaroids, standing roughly 4’x 9’ when framed, became a project known as The Faces of Ground Zero. It toured six cities in 2002, and then staged at Rockefeller Center in New York for the first anniversary of 9/11. It became a well-received book, the sales of which helped generate nearly two million dollars for the post-9/11 relief fund. The picture below is from its opening at Vanderbilt Hall in Grand Central Station. The touring exhibit was seen by an estimated two million people.

From the Project: The Miracle of Ladder Six

The South Tower had already fallen, and the same fate awaited the North. An urgent evacuation was taking place in that tower when six members of Ladder Six, the Chinatown Dragon Fighters, rapidly descending the stairs came upon Josephine Harris. An older woman, and hobbled by disabilities, she was going down slowly. In the time-honored traditions of firefighters everywhere, the six began to assist her descent. Bill Butler, strongest of the crew, helped her and talked to her. She mentioned her grandchildren. Bill assured her she would see them again. To do that, they had to keep moving — fast.

They all thought her slow pace of descent was a death sentence. But they hung together and resolutely stayed with Josephine. Upon arrival at the fourth-floor stairwell, she collapsed and urged the firefighters to go on without her. They refused. The building came down.

They’ve described it as a powerful gust of wind, accompanied by a giant rumbling, as everything around them came down in a massive rush of rubble and dust. Anyone, above them or below them, perished. Somehow, that fourth floor stairwell remained intact. Josephine’s pace of descent had placed them in the exact spot where survival was possible. Covered in debris, with fires spouting everywhere, and hemmed in a location that was at first impossible to discern, they eventually made it out. Every single firefighter in that stairwell refers to Josephine as their guardian angel.

Mike Meldrum, one of the Ladder Six team in that stairwell, said afterwards: “It was her just picking, I guess, the right spot. It was her time to say, ‘Guys, this is where we’re going to make a stand.’ I guess because she decided that was it.”

And, by protecting an unassuming sixty-year-old grandmother in poor health, hobbling down the stairs of a doomed building, they unwittingly saved themselves.

In an interview with Dateline’s Stone Phillips, Josephine said, “They are strong, brave, caring, and kindest people I have ever met. When I was scared, they held my hand. They took off their jackets and gave them to me when I was cold. They told me not to be afraid, they would get me out. And they did. They are magnificent.”

That’s what New Yorkers did on that day, and thereafter. They held people’s hands, comforted them, got them out. They brought them to safety.

Like all 9/11 stories, it does not end there. New York slowly returned to its normal rhythms. People picked up their lives. The firefighters of Ladder Six went back to doing what they do, saving lives and property. Josephine went back to her life in a Brooklyn apartment. It was a life that continued to diminish in the face of failing health and very little income. Ten years later, she was found dead in her home. At that point, she was so reclusive that her neighbors were barely aware of her death.

Her body lay in the morgue, awaiting a burial she could not afford. News of her death came to Ladder Six. Chief Jonas started working the phones. The Greenwich Village Funeral Home offered to take over the cost of the funeral. Church arrangements were made for a memorial mass for Josephine.

Ladder Six assembled. Once again, they carried Josephine, their guardian angel, this time to her final resting place.

“The Faces of Ground Zero, Portraits of the Heroes of September 11, 2001 Giant Polariod Collection”

These life-size Polaroids (9’x4’) were photographed in a studio near Ground Zero by Joe McNally shortly after September 11, 2001.

The photo subjects have become icons of the families of the victims, first responders, and others related to this tragic event and its aftermath.

This Collection is considered by many museums and art professionals to be one of the most significant artistic endeavors to evolve from the 9/11 tragedy.