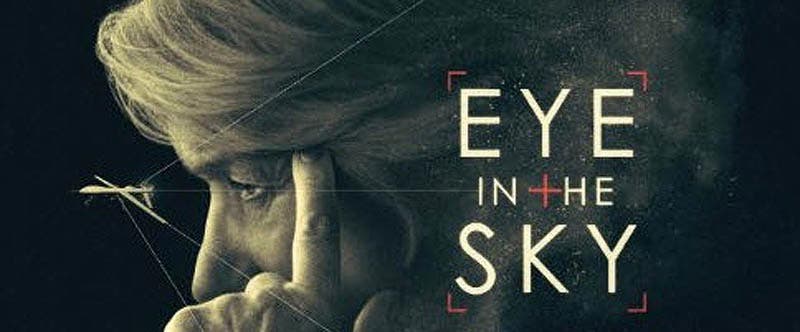

Academy-award winning director Gavin Hood’s latest film, “Eye in the Sky,” is a story about modern warfare and the use of drone technology. In the film, Hood (whose past works include Ender’s Game and Tstotsi) worked with an ensemble cast, including Oscar-winning actress Helen Mirren, Aaron Paul and Alan Rickman (in his last role) to tell the story of a top-secret drone operation to take down suicide bombers in Kenya. In addition to the star-studded cast, Hood also cast actual Somali refugees to help tell this story of digital warfare that spans four continents. Shot entirely in his homeland of South Africa, the film explores the steep political, legal, and moral price of every decision made during times of war. Adorama had a chance to sit down with Hood, for a one-on-one interview, where he takes us behind-the-scenes.

Q: “Eye in the Sky” was filmed on location, in your homeland of South Africa, were there any particular political challenges while making this film?

A: “There are no political issues from my government. What is politically interesting is that all the actors, the Somali actors that you see in the film, are not from South Africa because people from South Africa look very different than people from Somalia. So the Somali actors were all recruited from an area in Cape Town where thousands of Somali refugees, driven from Somalia by Al-Shabaab, are living as refugees. So the young girl [Aisha Takow, who plays the role of an innocent girl unknowingly in the the ‘kill zone’] is a Somalian refugee who’s applied for asylum in the United States. Her family fled after the horrors of Al-Shabaab in Somalia, and had to walk through five countries from Somalia to get to South Africa. The brother of the young man who plays her father was shot by Al-Shabaab, so these folks truly understand the fear and extremism of that organization and have fled their home country. Cape Town in South Africa is a constitutional democracy, we are not experiencing the kind of craziness that is going on up in Somalia, where it would be impossible to film, quite frankly.”

Q: How did you approach directing non-actors?

A: “I rehearsed with the non-actors for about, I think about four or five weeks. I worked with them just in terms of them understanding a how a film set works before Helen Mirren, or Alan Rickman, or anyone else arrived, so that they were ready for the experience.”

Q: Had they heard of these actors before?

A: “That’s an excellent question. I’d imagine that Armaan Haggio had because he’s been in Cape Town for a long time and his wife is a singer. And that’s one of the reasons they left Somalia, because she’s a singer and Al-Shabaab bans music, can you imagine? So all I would say is that the actors that you see in the roles of Somalis – even Barkhad Abdi was in Somolia when he was 7 before escaping to Yemen, and then ultimately the United States – for these actors, the film is not theoretical, it’s grounded in their own reality.”

Q: So putting them in the public spotlight kind of gives them voice now for their political causes that they might not have had before?

A: “I would be weary of using the term political causes because I will say that many people who came to auditions, when they heard that the subject matter involved Al-Shabaab, they left because they were afraid. So I’m not sure that these people are seeking the spotlight, per se, they’re trying to make a living as refugees in a country with considerable struggle in their lives. And Armaan and his wife were entertainers in Somalia, and so he was just so thrilled to have a role as an actor in a movie where there’s a Somali role and Somalis being represented as real people not sort of a stereotype of ‘terrorists.’ And those are the sort of things we spoke about, but I’m not sure he… I don’t want to speak for him…it’s a life and death situation with Al-Shabaab.

I am proud of the work that real Somali people do in this film. As actors who have not, for the most part, worked on film. I’m just really proud that they are in the film, agreed to be in the film, and deliver performances that I think measures up with the great actors like Helen Mirren and Alan Rickman. They bring their emotional truth based on real experience and my job as a director was to simply give them the space to allow the emotions. Emotions based on their very real experiences of fleeing Al-Shabaab and coming to Cape Town to live hard lives. They, intuitively, as human beings understand the tensions expressed in the film and my job as a director is to, frankly, to help them not to act and to give them permission to be simple and truthful in the moment. And so that’s what rehearsals were about, about just peeling away the inhibitions that non-actors come with where they think they have to perform. Where what they really have to do is step up and deliver an honest response moment by moment with the other actor in the scene and to respond and listen to the actor.”

Q: That’s interesting that you talk about that kind of ability to react to the other actor, but many of your scenes were shot on green screen with the actors not being in the same room.

A: “Yes, but that was with more professional and seasoned actors. That’s a great point, so the seasoned and experienced like Helen Mirren, Aaron Paul, and Alan Rickman, were actually not even in the country at the same time. I think Helen and Aaron sort of met on the last day, as she was leaving and he was arriving, and maybe they said hello. But that was simply for budget and scheduling reasons, the actors were only available for certain times, so I had to juggle my schedule to accommodate. As bad luck would have it, Helen drew the short straw. She was the first one up , nothing else had been shot, there’s nothing on her screens except green, and she’s reacting to a little red cross. I’m describing to her what is happening. And I’m trying to describe it at a pace and with simplicity. For example, the missile strike. I’m describing when the missile goes through, how the child is hit, whether she gets up, if she gets up, if she moves. Helen is simply watching a red cross and using her imagination to reveal feeling, and that’s what actors do.”

Q: You made a film about drone technology, and you also used drones to actually make the film. Can you tell us how you feel about the controversy to regulate drone cameras for public use?

A: “I think we are going to have to regulate it because the next step in the evolution of drones is tiny drones becoming armed. I don’t know how we regulate it and control it. I think where this technology is going is potentially quite unsettling. So the teeny, tiny drone you see in the movie at the moment is simply a surveillance drone, but the minute that little drone is weaponized, which is not difficult to do – add an explosive charge to that drone, add face-recognition software – and already those drones can fly in formations, as swarms, knowing where each other are. You can see that on Ted talks, there’s a whole demonstration of tiny drones. So the push is for what they call swarm theory, which is multiple tiny drones, hovering over a battle field, targeting individuals, either as little drone explosive devices or if being used for an assassination, with anthrax as they fly by you they spray your nose. I mean it’s kind of creepy. So do I think we need to do everything we can to find ways to minimize the crazy proliferation of what could potentially be weaponized tiny drones in the hands of anybody? Yes, I actually do. How that regulation should be drafted, I don’t know. As a filmmaker, when I go to South Africa, it’s very simple. As filmmakers, we’re not special, we need permits to fly. In my own country, a small drone flown by a member of the public nearly downed an aircraft in the airport because they were flying too close, and an accident was narrowly avoided. Literally, on the first week we arrived to start shooting, the South African government banned all drones from flying. All drones. They just said, “Nobody flies a drone!” It was pretty extreme. We are not going to risk an accident with people just flying their toys wherever they feel like it. They shut it down, and we went “oh boy!” because we were using drones with cameras. So we had to make special applications, we had to show what we doing with our drone. And that’s fine. Anybody that objects to that is being very selfish. We don’t just walk into someone’s property and start shooting, we get permits and permissions to use locations. But what we need is a clear process, where you can apply so that filmmakers are not held up. We want the bureaucracy to be minimized. But, I don’t think just because filmmakers want to use cameras we should allow everyone to fly drones unregulated close to airports, potentially armed and spy on their neighbors.”