Many years ago, I mentioned to my mom that I was taking a darkroom class. She walked to her bedroom closet, pulled down a shoebox, handed it to me and said, “Your dad took these.” Inside were hundreds of photo negatives.

My dad died when he was just 43 years old and I was eight. I flashed back to my parents’ old photo albums. When I was a kid, those heavy volumes felt like ancient relics. They had fragile black paper pages and deckle-edged prints that popped out of their mounting corners no matter how carefully I browsed. Now, I was the caretaker for this box of photo negatives and had no idea what to do with them.

I owned a basic enlarger and knew these large single-frame negatives wouldn’t fit in my standard-issue 35mm holder. I put the shoebox back into storage, but the idea of working with them stayed with me. Years later, the box tumbled into a massive basement flood. Panicked, I dumped the negatives into a bucket with water and Photo-Flo. Then, I strung them back and forth between the walls of my house to dry. Many of the negatives’ corners still bear diagonal clothespin scars from that rescue mission.

During the 2020 pandemic, I—like many others—found myself with unexpected time on my hands. While some people used this opportunity to de-clutter their closets, I only pushed away a stash of holiday ornaments and a pile of sweaters to reach the shoebox stored on a high shelf. I still didn’t know how to approach the project from a technical standpoint. But I was finally ready to figure it out.

Weighing the Options

I read everything I could find about best practices for scanning vintage photo negatives. The three options most cited were to send them out for professional drum scanning, mount a DSLR in a copystand arrangement, or use a flatbed scanner. While each method has its distinct pros and cons, I decided a flatbed scanner was my best choice given the number of images in the collection. Plus, I had a desire to be entirely hands-on with the process.

Once that decision was made, I discovered my most daunting technical challenge: the negatives themselves. Nearly all were irregularly hand-cut individual frames. Many had severe curls, thumbtack holes and other physical flaws that defied attempts at fitting them into standard holders or laying them flat. As I dug for solutions, I learned about fluid mounting—a process that sandwiches the negative between a mylar sheet, anti-newton glass, and a liquid. This time-honored technique was entirely new to me. But, once I gave it a try, it was taming unruly negs and coaxing the best possible quality from the flatbed scanner.

Fluid mounting was a revelation. Based on what I’d read, I expected the process to be time-consuming and fiddly. Instead, it was a lot of fun. Maybe it’s the smell of the chemicals, but it brings back happy memories of working in a conventional darkroom. Armed with an Epson V750 Pro scanner, a variable-height mounting station, and a fluid mount supply kit, I started on a journey that would take the better part of a year to complete.

Photo Discoveries

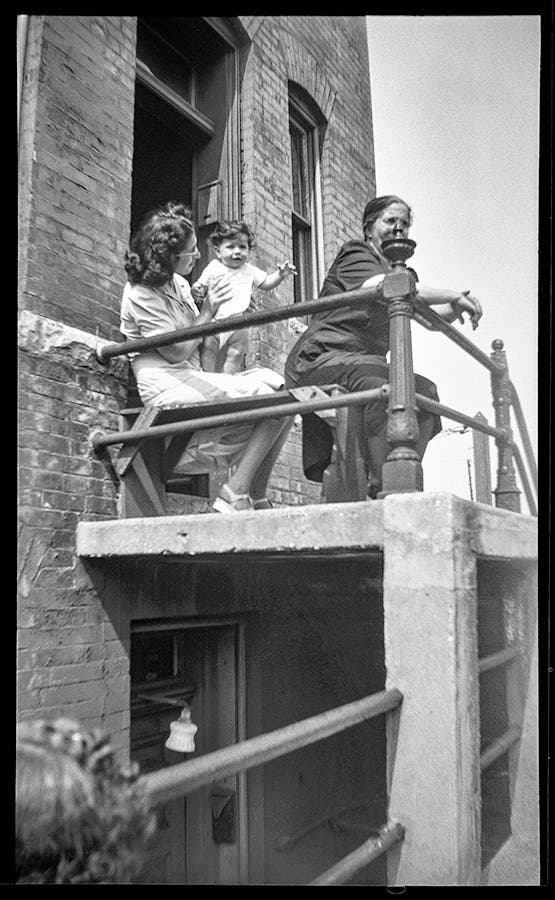

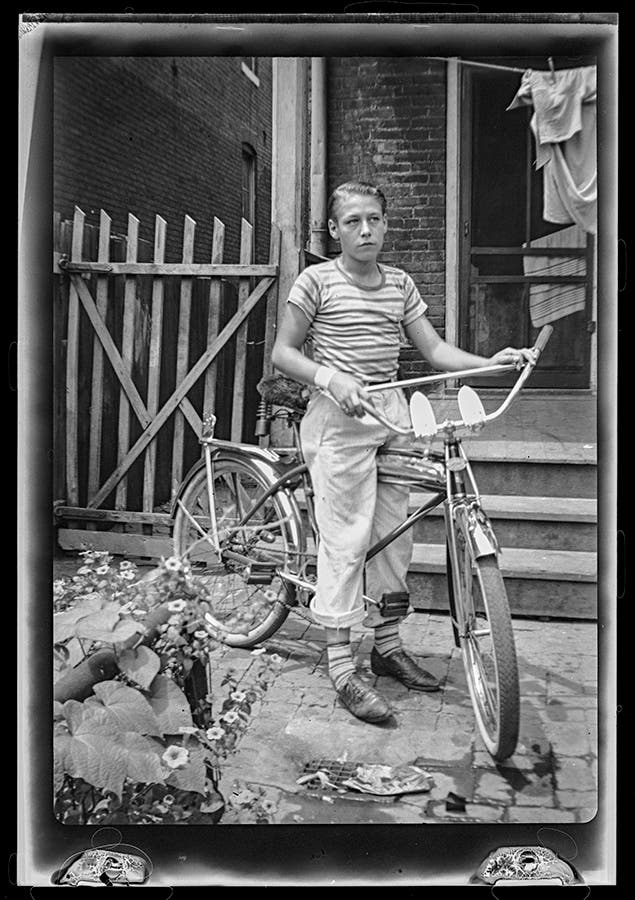

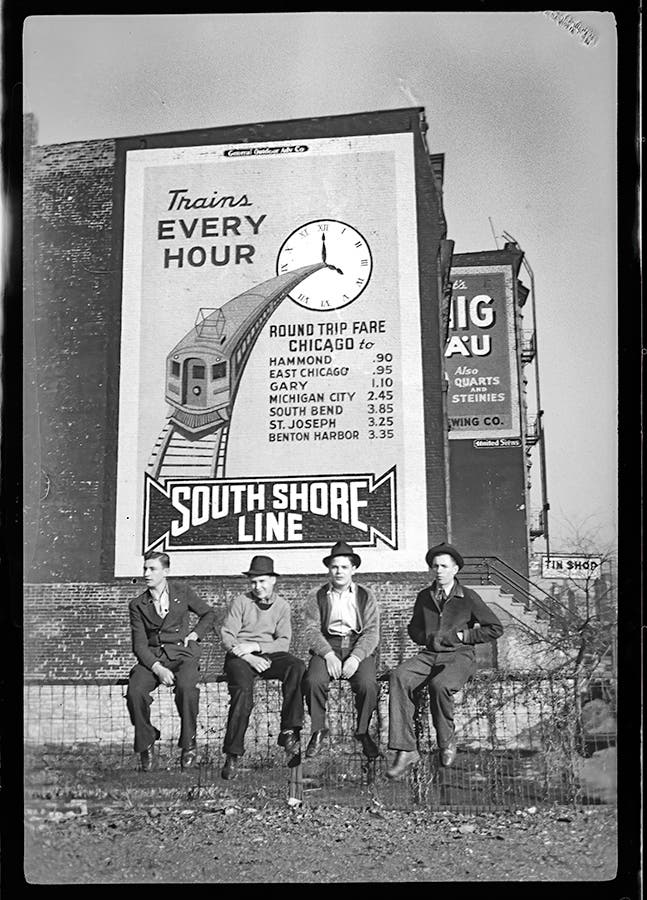

As I culled the negatives, I found that my dad took most when he was quite young—not long after his high school graduation in 1939. A lot of the images show guys doing guy stuff: climbing up on billboards, mugging for the camera, standing next to cool cars they likely didn’t own. It feels like easy camaraderie in the scenes my dad captured, reflecting his life in a working-class Chicago neighborhood just before America’s entry into WWII and his joining the U.S. Navy where he served as a radioman on a minesweeper.

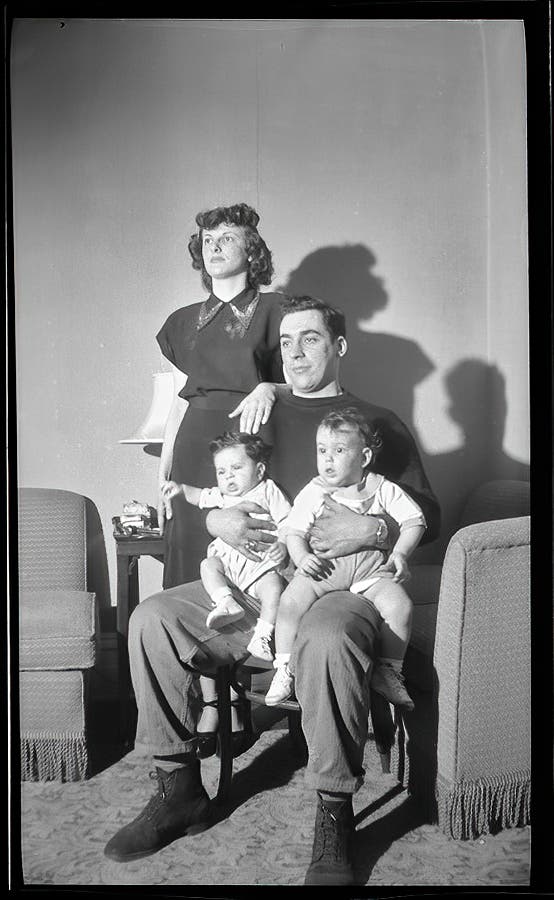

Months after I’d culled the collection, my sister discovered another batch of our dad’s negatives while cleaning out a storage room. This batch was smaller than the first, but the notable twist was that these newly found images were all captured after my dad’s 1945 return from the war. I’ll never know how or why the pre-war and post-war batches separated. What’s clear, though, is a distinct lifestyle change. Instead of depicting buddies making human pyramids at picnics and posing with girlfriends, the photos tell the story of marriage, babies, and a move from the city to a new house in a suburban wilderness.

Staying True

Many photo negatives in the collection don’t have corresponding prints in our family’s photo albums. But there are a few, and their dimensions suggest they were contact prints. For that reason, I committed to leaving the compositions as close to their original state as possible. If my dad didn’t have access to an enlarger, I wanted the finished images to stay true to his reality. Another decision was to keep fixes (for flaws like scratches and nicks) to a minimum and concentrate instead on pulling as much detail and tonal range as possible via Capture One and Photoshop. Each frame presented a unique set of challenges in terms of physical condition and exposure. Some took hours to process while others took days.

Sharing the Photos

Once I had processed the core of the collection, I tentatively shared a few photos on my Facebook page. I didn’t expect much of a response from acquaintances with no connection to my dad. To my great surprise, the feedback was immediate and overwhelmingly positive. That gave me the confidence to cast a wider net and today The Shoebox Negatives have been seen across the globe.

Learning to evaluate the images based on merit versus sentimentality isn’t easy for me. And to be honest, I’ll probably never be truly objective about any aspect of this project. Although, I’m getting better at it. The response from people outside my circle of family and friends continues to offer valuable insight into what works and why.

My original mission for The Shoebox Negatives was to figure out how to bring them to life. That’s a work in progress. In the meantime, the parallel goal is to have them seen. But at the heart of it, the best part of this project—and the part that really counts—has been discovering which tiny slices of my dad’s life he felt were important enough to capture on film back when cameras weren’t in every purse.

The shoebox became a window, and there’s still so much for me to see.

See more photos from The Shoebox Negatives below: