These days, we all (well, most of us, anyway) love working and playing in the digital darkroom. However, before we begin having more fun with our travel photographs in the digital darkroom, there are two important aspects of digital imaging we need to understand. One is Image Size. The other is Save As, also known as File Format.

To illustrate my points, I’ll use a photograph I took on a June 2004 trip to Arches National Park in Utah.

I’ll work in Adobe® Photoshop ® Elements, sharing screen shots I captured with a program called Snapz X Pro. (Hey, if you want to see some other my pretty pictures from my trip first, scroll down to the end of this article. But come back for “must-know digital darkroom info.”)

Let’s begin with Image Size, which we get to on the Menu Bar by going to Image > Resize > Image Size.

For newcomers to the digital darkroom, understanding picture size can be confusing, because we simply can’t look at a picture as a 5×7- or 8×10-inch print, and so on. There are new factors to consider.

But first, let’s take a look at the size of a digital file straight out of the camera.

Here’s a look at the original Image Size dialog box for the image. It’s typical of the dimensions of a High/JPEG image from high-end consumer digital cameras, that is, the images has a width and height of more than 20 inches, and a resolution of 72 PPI. You’d never make a print that size with that resolution. It would look terrible (very pixilated). However, when properly resized for a print or for emailing, it will look great! Read on.

In Photoshop Elements, there are basically two different ways to view and manage the size of a picture:

• In pixel (picture element) dimensions (top red arrow). These dimensions show Adobe Photoshop Elements’ calculation in pixels of the image’s height and width with file size shown as a number of kilobytes (k) or megabytes (M);

• In actual document image size (blue arrow). Inches are shown in this screen shot, but clicking on inches (the default setting) reveals other size choices, including centimeters and millimeters. For most practical purposes, we only need to pay attention to the Document Size and only need to work in inches.

Compare this screen shot to previous screen shot of the Image Size dialog box. You’ll see that the Pixel Dimensions are the same: 9.46M. However, the Document Size has changed to 5.25×7 inches with a Resolution of 300 PPI, which is an idea size for making an inkjet print. I did that by unchecking the Resample Image box and then by typing in 300 PPI in the Resolution window (see my bottom red arrow). I could also have typed in the new dimensions, which would have changed the Resolution.

Hey all you Brits and Canadians and others who use the metric system: As I said, you can view the Document size of your image in other methods of measurements. You do that by clicking on the blue up/down arrows. That’s how I got a to see the size of my image in centimeters.

File Size Basics

Basically, you want a large file for printing and for publication, and a small file for e-mailing. Large files contain more data, which is necessary for making high-quality desktop prints.

However, large files also take a long time to send over the Internet as e-mail attachments. Small files don’t contain a lot of data, which makes them a poor choice for printing, but a good alternative for e-mailing. To avoid starting off with a picture with a low resolution, set your digital camera to either the High/JPEG, FINE/JPEG or, better yet, the uncompressed TIFF or RAW setting if that choice is available.

My 5.25×7 inch image with a resolution of 300 PPI is way too large for e-mailing. To reduce the resolution, I typed in 72 in the Resolution window. Now the image is the same size, but with a lower resolution and less data.

These two versions of my picture show the difference between a picture with the same dimensions, but with different resolutions. The “pixilated picture” is the image made at 72 PPI. This is how a low-resolution image will print.

There’s another reason for downsizing the resolution of an image: filters are applied much faster to small files than they are to large files. So, when experimenting with new filters, play with them on low-resolution images.

Let’s go over the Resample Image one more time. Again, I admit it can be confusing for the new comer to Elements. If you want to change all the Document Size settings, uncheck Resample Image. When you do that and type in new numbers, the other numbers change proportionally (see that that boxes are locked). This is a fast and easy way to make larger and smaller prints – and to find out the new resolution of a picture.

Enlarging the picture size reduces the resolution. In this case, too much to produce a good desktop print.

Decreasing the picture size increases the resolution. In this case, we can make a good desktop print from it.

Save As

Now let’s talk a look at the Save As command, the way we save our pictures.

After all your hard work in the digital darkroom, you don’t want it to go to waste. That can happen if you save a picture in the wrong format. That’s why it is important of save your pictures in the right format.

In the Menu Bar, go to File > Save As

When you select Save As, the Save As dialog box opens, revealing all the different ways that you can save a photo. JPEG and TIFF are the two most useful formats. Here’s the scoop on each.

JPEG. This format was designed to discard information that the eye cannot normally see. The greater the compression ratio (an option when saving a picture as a JPEG file), the greater the loss of image quality and sharpness.

The JPEG format is great for sending files over the Internet and for posting pictures on Web sites because the JPEG format compresses an image when it is closed (so it can be sent quickly), and then decompresses it when it is opened (so it opens fast). Because some data can be lost—JPEG uses strong compression techniques—all that compressing and sending and decompressing can corrupt, or damage, pixels in a picture – resulting in a loss in image quality.

The real visible damage is done to a JPEG file when it is opened, enhanced and saved, and then reopened to begin the process once again and re-saved. Do that several times and you will notice a reduction in image quality. Do that just once, as you may do when you transfer your JPEG files from your camera to your computer, and you will not notice any difference. But be sure to save your pictures immediately, even before rotating, as TIFF files for the best possible quality.

One advantage to JPEG files is that they don’t take up a lot of memory in your computer.

A disadvantage of JPEG files is that, due to the format’s compression technique, you can’t save a picture in Elements that has Layers that you have created In the JPEG format, all the layers are merged into one.

TIFF. TIFF (Tagged Image File Format) is a lossless format. You can open, work on and save an image countless times without any loss in quality. When you save a TIFF file, you are also saving all the Layers we may have created. So, you can go back to the image again and again and make changes to our heart’s content.

TIFF files consume much more memory and hard disk space than JPEG files, so if your serious about saving your picture files, beef up your computer’s memory or get a supply of CDs or DVDs on which to store your pictures.

So, think before you type in new numbers in the File Size image size window and click in the Save As window. Choose your File Size and Save As format carefully. And remember, edit only on copies of your original images so that your original is always left as your “digital negative.”

Okay, for all of you have scrolled down (as well as those of you who actually read all that stuff about PPI), here are some pretty pictures from my trip, along with some photo tips.

Double Arch, Arches National Park, Utah – Use a polarizing filter to darken the sky when the sun is off to your left or right.

Bryce Canyon National Park, Utah – You can take panorama photos with any digital camera. Simply compose a shot with a panorama in mind. Use a wide-angle lens or wide-angle setting on your zoom lens and plan to crop out the top and bottom of the frame.

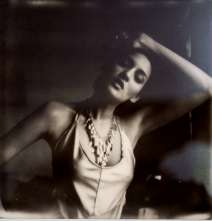

Bryce Canyon National Park, Utah – Want create pictures with a unique look? Consider infrared photography. If you have a Canon D30 or D60, or Nikon D100, there’s a guy who can make your camera an IR-only camera. Contact him at Irguy@irdigital.net or see his site: www.irdigital.net.

When composing a landscape, vary your position. Moving even a few feet can make a big difference in the impact of the photograph.

Rick Sammon is the author of The Complete Guide to Digital Photography, published by W.W. Norton. He also recently completed two interactive CDs, Photoshop for the Outdoor and Travel Photographer and Photoshop Makeovers, distributed by Software Cinema. For information, see www.ricksammon.com