An acclaimed photographer based in Brooklyn, New York, Robert Clarkhas created an impressive body of work that transcends genres—he is equally adept at portraiture, photojournalism, creating images for advertising, and a broad spectrum of documentary work. His abiding passion is documenting the evolution of the human species, creating compelling images that merge his fascination with science and paleontology, his brilliant command of composition, and his masterful use of lighting.Clark has won numerous international awards, and his work has graced the pages and covers of such prestigious magazines as Time, Sports Illustrated, Vanity Fair, Stern, Discover, and U.S. News and World Report. He has photographed 40 articles and more than a dozen covers for National Geographic, and his National Geographic article, “Was Darwin Wrong?” earned the National Magazine Award for best essay in 2005. The unforgettable images he shot on 9/11, including one of the second plane hitting the tower, were published worldwide, and his coverage was honored with a first place World Press Award in Amsterdam. Robert Clark continues his close association with National Geographic and is working on a book documenting the science of evolution.

To give you a clearer picture of this exceptional photographer, lecturer, and workshop educator, who he is, and his mission, we interviewed him just before he flew off to Cambodia on his next assignment.

Q. Was there any photographer or type of photography that influenced your work or inspired you?

A. I was very fortunate to be able to work with Greg Heisler, a great educator, a consummate master of lighting, and the smartest photographer I have ever met. One of the greatest things he taught me is that for every story there’s an appropriate response to how it needs to be told. I’m also a big fan of Irving Penn and Albert Watson, both of whose work encompassed a huge arc—they were able to do still life, fashion, portraiture, and much more. Maybe that’s one reason I’ve always been interested in, and have actually done, a heck of a lot of different things. But lately, I’ve gravitated toward creating images that reveal the amazing field of evolutionary biology.

Q. You mentioned that you exercise a fair amount of control over your work, which is certainly a big plus for a creative photographer who captures documentary images that rise to the level of fine art. What exactly do you mean by that, and what has enabled you to achieve that degree of relative autonomy as a freelancer?

A. I was a big fan of Walter looss, the renowned photojournalist known for his images of sports legends, and, as I mentioned, Greg Heisler, who had a huge influence in the way he taught me about lighting. Greg’s approach to lighting and telling a story is ‘intellectual emotional,’ and he knows how to make people look where you want them to look. Perhaps that’s why nobody at National Geographic tells me what to take a picture of or how to light it. Of course I am incredibly fortunate to be working with some of the smartest and hardest working photo editors in the business.

Another aspect of my approach to photography is that I see learning new things as an essential part of my personal evolution as a photographer. I’ve often started working on stories I didn’t know enough about, but by the time I was done, I knew all about the subject. My stories on Darwin, and Alfred Russell Wallace, perhaps the greatest field biologist ever, come to mind.

Q. What camera, lenses and equipment do you typically use for your current work?

A. A Nikon D800 with Nikon 14-24mm f/2.8Gand Nikon 24-70mm f/2.8G Zoom Nikkor lenses, a Zeiss 100mm f/2 Makro Planar ZF.2, and two Sigma Art lenses, a Sigma 35mm f/1.4 DG, and a Sigma 50mm f/1.4 DG, both of which are extremely sharp.

Q. When did you first become interested in photography as a mode of expression, an art form, or as a profession? Did you have any formal education in photography?

A. I started shooting when I was 16, and I immediately knew that that’s what I wanted to do. The fact that my brother was the editor for a local newspaper made it an easy choice. My mother gave me my first camera, anentry-level 35mm SLR, when I was 16, and that’s where it all began.

Narrative journalism is what I was interested in primarily. Indeed, I have a degree in photojournalism from Kansas State University, but I would classify my present work more as documentary than as journalism.

Q. Your amazing picture of a rhinoceros is straightforward in a certain way, but it manages to be almost surreal in the way it captures the visceral presence of this enormous beast, as well as its beauty and strangeness. What were you trying to achieve with this incredible image and was it shot by available light?

A. What I try to achieve with images like this is clarity and a dimensional quality, a look that gives you the sense that you could actually pick the subject up, that it is 3D even though the medium is 2D. This was an image for a story about Alfred Russell Wallace, the first person to write a scientific description of the Sumatran Rhino. I simply hung a strobe to enhance the lighting, went outside the pen, and took the shot when they let her in and she was standing in the right place.

Q. The iconic image of a “whitewashed” figure wearing a pointy hat, posed in front of what looks like a brown earthen wall with what looks like a noose around is neck is kind of creepy, but it also has a certain majesty that takes it to another level. Who is this person and what is the significance of this image?

A. This is an image of the famous mummy called the Tollund Man and he dates from the Iron Age II, or around 2500 years ago. It’s significant because it is one of the oldest categories of mummies called Bog Bodies that have been preserved by being thrown into a bog, where the tannins in the soil literally tan his hide. Clearly he was murdered, but we don’t know why or by whom. I travel with lots of lighting equipment and I work with museums so I’m able to spend a lot of time with subjects like this to achieve what is, in effect, a dramatic and beautiful portrait. I see my role as the exact opposite of a writer, who usually wants the reader to move through the material quickly. As a photographer I want to stop them in their tracksand engage their mind and emotions.

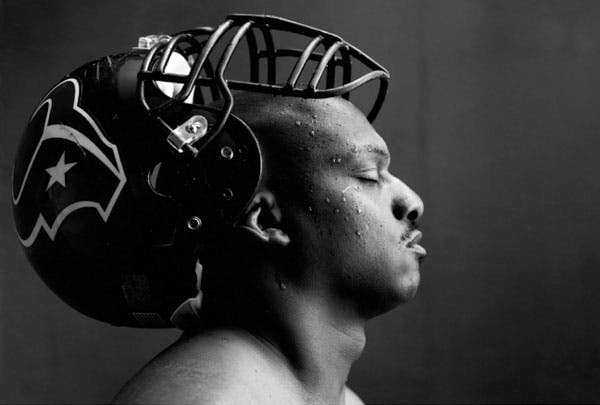

Q. Your black-and-white image of a football player with his helmet and face mask hanging off the back of his head, his eyes closed in a kind of reverie, and what looks like sweat pouring down his face is definitely not a conventional sports portrait, but it somehow conveys what being a football player must feel like. How did you shoot this engaging and emotional image?

A. This portrait of an All Pro defensive lineman was part of a series on football players I made for The National Museum Of Fine Arts Houston (NFAH). All these images were carefully set up and composed, and shot on 4×5. I grabbed this guy after a game and shot 20 frames of 4×5 film; my aim was to get a close look at these pro athletes and what they do. The fact that I was able to convey his life and the emotions that go into it is due to the influence of Greg Heisler, the ultimate lighting master, and the man who inspired me to move to New York City to learn how to become a portrait photographer. Indeed, I’m proud to say this image looks like some of his work.

Q. When you look back on all your notable achievements as a photographer, what is it that gives you the most satisfaction?

A. Basically that I’ve learned a lot, traveled a lot, worked hard, and created something that others think is worthwhile. As a dyslexic kid from Kansas, I’m not exactly the type of person you’d expect to have the career path I’ve been able to take. However I do have an incredibly good work ethic, I’m willing to learn, and I don’t make the same mistake twice. Working hard on a daily basis is fun, and Iget to do things no one else in the world gets to do, like photographing Darwin’s birds in the Galapagos. It’s an honor and a privilege, and there’s a lot of responsibility that goesalong with having that opportunity.

See more of Robert Clark’s work:

Website:http://www.robertclark.com

Instagram: @robertclarkphoto

Tumblr:http://robertclarkphoto.tumblr.com/