Her Mission: Revealing the State of the Planet One Shutter Click at a Time

In October of 2016, Iowa City-based photographer Tama Baldwin joined the Arctic Circle’s expedition team of artists and scientists sailing around the island of Svalbard to explore sites of human habitation in the high arctic, and she is currently involved in documenting encampment of Native Americans from approximately 300 tribes at the Standing Rock Reservation in South Dakota to defend the Missouri River from the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL).

The overarching theme of Baldwin’s images is revealing what happens when human institutions and technology come into contact with wild nature in its original state. To that end, she seeks out everything from pockets of wilderness embedded in the largest metropolises, to traces of human presence in the most remote wildernesses. Her stunning images range from abandoned cities and dissolving roads to the ruins of lost civilizations, and wilderness areas rebounding from industrial injury.

In short, the subjects that draw her eye show the progress and restorative ability of nature, the planetary destruction wrought by our species, and everything in between. She sees the explosive growth of the human population— 200,000 new inhabitants each day—as a testament to our ingenuity and ability to innovate and also our rapaciousness. That’s why she describes her landscape work as Landscapes in the Anthropocene, the unofficial name for our geological era popularized by Nobel Prize-winning climate scientist Paul Crutzen. The new word reflects the substantial impact our species has had on the planet since the dawn of the industrial revolution. Here are the details of two of Baldwin’s latest projects.

The Black Mirror: Accelerated Warming of the High Arctic, Svalbard Archipelago.

The Black Mirror is an ongoing photographic project featuring tidewater glacial fjords on the very northern tip of the Spitzbergen, the largest island on the Svalbard archipelago at 79.46 degrees North. Between these shores and the North Pole, there is only open ocean water and pack ice. Baldwin’s group arrived at the end of the archipelago in the middle of October 2016, on the eve of the polar night. During their ten-day sail northward the available light was growing noticeably briefer, and by the time they reached Smeerenburg, the ruins of a Dutch whaling station established at the beginning of the 17th century, the sun was not going to clear the mountains to the east again for another four months.

Observations on a Warming Polar Climate

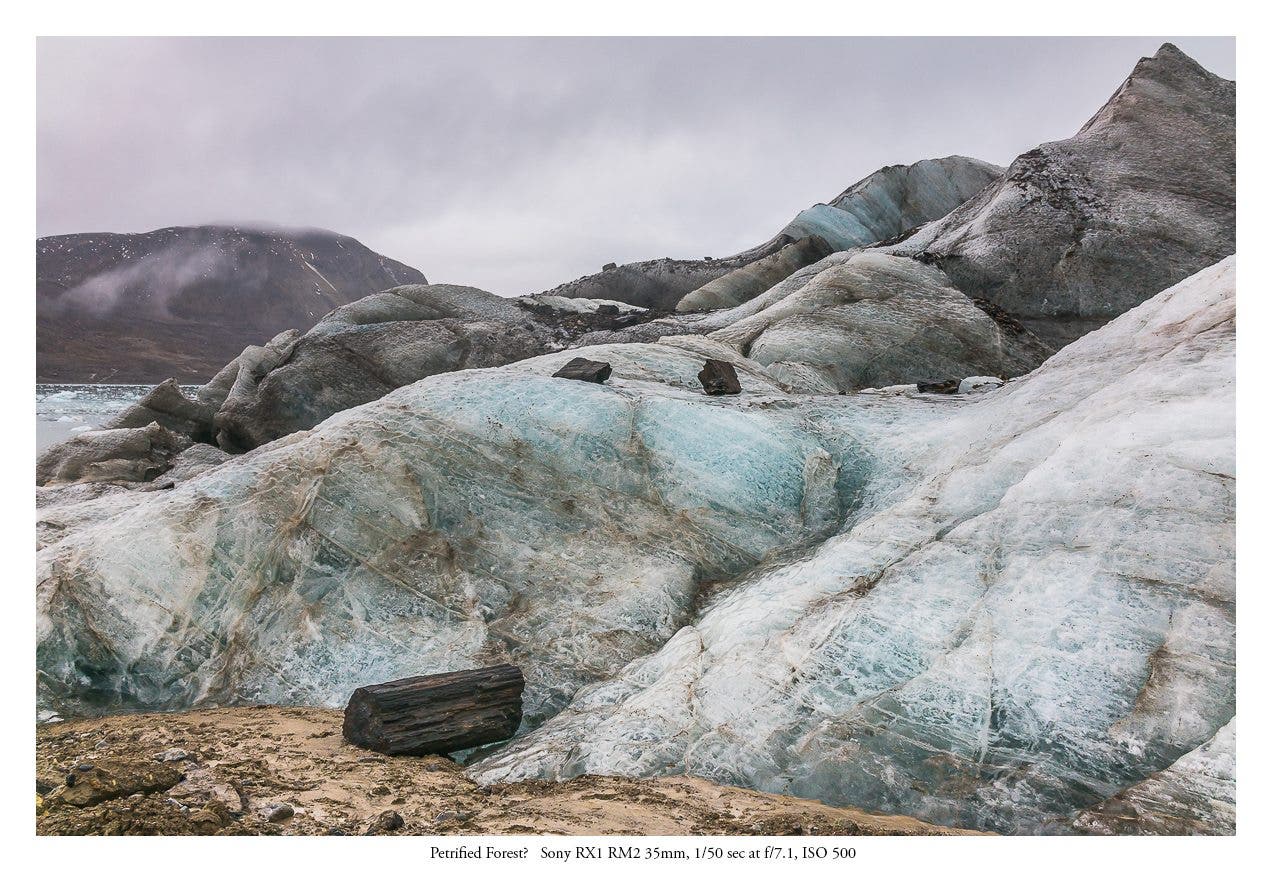

“Even though it was officially the beginning of winter,” Baldwin recalls, “the few brief snow squalls always gave way to long warm rains that erased the snow from the mountains, a process that intensified the banks of fog rising off of the glaciers. We worked in twilight much of the time in a blue-grey gloaming infused with the compressed light of all that ancient ice, some of which fell as snow 100,000 years ago. We made two landings each day when the weather allowed, accompanied by four shotgun-bearing women who served as polar bear guards and a dog named Nemo who kept watch over the deck. Each day we kept waiting for the snow to return, and each day the warm rains only intensified. I have been the arctic many times, and this is the first time I watched polar bears and arctic foxes in winter moving through muck and mud, their white coats so starkly contrasting the dark earth. One afternoon I waded through deep mud, almost up to my knees, to reach the top of a very large glacier. I noticed what looked like large chunks of trees that no one had seen or read about before. They were evidently petrified trees that had grown there the last time the arctic was more temperate, 60 million years ago! By the end of December, what we were observing what had been predicted by climate change scientists: 2016 was the first year in recorded history that the high arctic territory of Svalbard had an annual temperature average above freezing.”

On the edge of the Standing Rock Reservation, which runs along the Missouri River right across the North Dakota border into South Dakota, there is a legal encampment of Native Americans from approximately 300 tribes around the United States standing in solidarity with the Sioux of Standing Rock. In December 2016, they were joined by thousands of veterans, some recently returned from the Middle East. Their goal: defending the Missouri River from the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) that is currently being forced through territory granted to the Sioux by treaty in the 19th century. Originally, the pipeline was to cross the river to the north but that plan was scrapped because the pipeline posed a threat to the water supply of Bismark, the state capital. The rerouting was done without the legal approval of the people of Standing Rock, in spite of the fact that the current plan requires the destruction of significant archeological sites, cairns, burial grounds, and other lands sacred to the Sioux. The North Dakota State Police and the Morton County Sheriff’s Department, with input and approval of the governor of North Dakota (who owns shares in the pipeline as of this writing), have now been engaged for over six months in a military campaign against the people defending the watershed where it passes through Sioux land. The Army Corps of Engineers, which originally halted the project, have now given their final approval, and that may lead to further conflict and confrontation.

Observations on Standing Rock

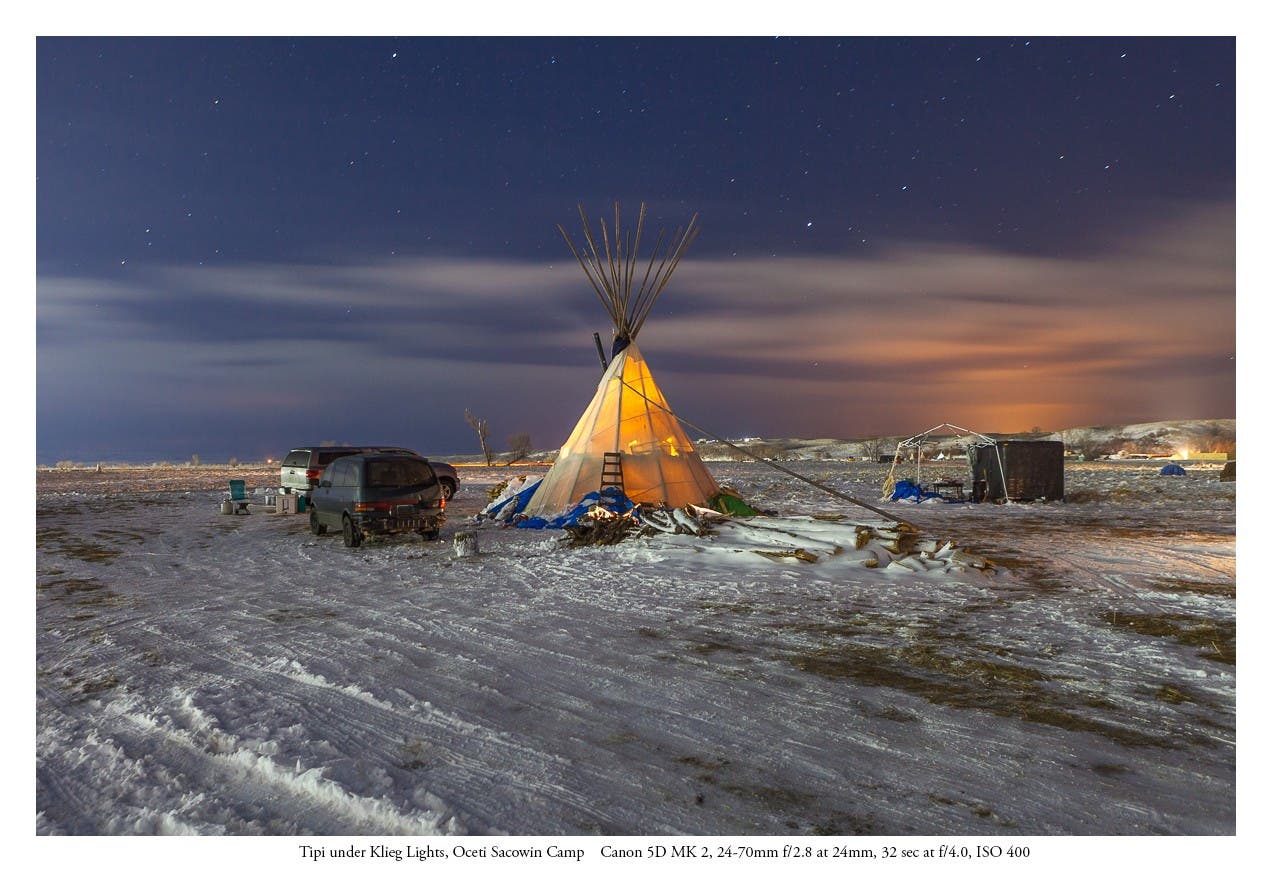

“We first arrived in camp after nightfall, and one thing that struck me immediately was the brutal glare of klieg lights lining the horizon. I was told that they had been erected by the Army Corps of Engineers to harass the people living in the camp, to disrupt their ability to sleep, which struck me as ironic since the camp is devoted to prayer and ceremony, and no alcohol, weapons, or drugs are allowed. At dusk and dawn, there is drumming and songs and prayers offered to the earth and to everyone on both sides of the conflict, the police and the water protectors as they like to call themselves. Lately I’ve been devoting a lot of time to the issue of the absence of natural darkness—what some would call light pollution—but this was the first time I encountered artificial light being used as a psychological weapon—and to defend an oil pipeline at a time we desperately need to be moving on toward renewable energy sources. Worse yet, I had just returned a few weeks earlier from Svalbard where we had witnessed the impact that the warmest year in recorded history has had on the high arctic. At Standing Rock, I felt like all my recent photographic projects were dovetailing. I set up across from Turtle Island, a beautiful bluff above the Missouri River, yet another sacred Sioux site that is slated for destruction by the pipeline. It was very disorienting to see a religious site wrapped in razor wire under klieg lights and patrolled by police in armored vehicles for something that seemed so unnecessary and so potentially destructive. Entering the camp at night I felt like I was driving into the past and the future simultaneously. The horrors Native Americans have been enduring for centuries were not only still alive and ongoing, but as police violence has escalated both Amnesty International and the United Nations are now investigating. Nevertheless, I fear I was witnessing our collective future, one in which the right to free speech and peaceful assembly has been criminalized.”

To see more of Baldwin’s work visit her website at: www.tamabaldwin.com