There is no such thing as a golden rule when it comes to portrait photography. I can’t simply hand anyone a “one size fits all” solution to become a portrait photographer. What I can do is share my personal experience and the information I’ve picked up along the way to becoming one.

Although there is no right or wrong way to make a portrait, there are definitely certain standards, trends and directions in this genre of photography. Starting out, as long as the photograph is well thought out, and you considered all the elements in your viewfinder, then you are on the right track.

There are many different approaches to taking a portrait, and one is not necessarily more “pro” or “amateur” than the other.

Candids

Candid portraiture is made without any prior interaction between the photographer and subject and is often taken without their knowledge. This approach comes directly from street photography and was started back at the beginning of 20th century by photographers like Robert Doisneau. His black and white portraits of Parisians are still as fresh as they ever were, and it’s often hard to believe that they were not posed.

I think that’s the trick with street portraits. Everyone has his/her own approach. My technique is to “find and wait.” When I see a situation that can potentially become a photograph, I wait for my “model” to look directly at the lens. Sometimes I wait just for a second, sometimes for a long time, almost trying to provoke the glance.

To make the photograph of the young horse trader, I kept coming back to the same spot throughout the day, waiting for everything to align the way I liked it. Once it did, I just waited for the boy to look at me – it happened and that’s when the decisive moment took place. On the other hand, the photograph of Norman was just a matter of being at the right place, at right time. The moment he saw my camera, he ducked away from the lens, but as I was waiting for his glance, I released the shutter and there was my photograph.

This approach works especially well in busy situations, at events, and in crowded areas where permission to photograph is not required. I encourage you to try it and see if it might be the approach you enjoy.

This, of course, is not the only approach and some photographers might have the completely opposite idea when photographing people. If you are not aware of Bruce Gilden’s work, you should check out his portfolio to get a better feeling for opposite end of the spectrum. He made many of his portraits from a distance of barely a meter or so using a wide angle lens and handheld flash – this is not for everyone but it shows how the personality of the photographer shapes his approach and portraits he will produce.

Maybe try this approach with people you know first, at a house party or family gathering to have a different perspective on the events. See how these photographs will be different from your other portraits. You might even try going wider than is usually “accepted” and use a fish eye lens.

Environmental Portraits

There are other photographers that excel in candid portraiture, including Mary Ellen Mark . Mark’s work ventures more into environmental portraits, which I think is located somewhere on the intersection of candid and constructed portraiture.

The godfather of environmental portraits is Arnold Newman. Many of his portraits shaped how we see certain people, and for starters, his portrait of composer Igor Stravinsky is a great example of Newman’s approach – the subject is closely tied to the environment and its elements. It is also a great lesson in how different the initial vision is compared to the final photograph. Newman extensively cropped this image, significantly changing the aspect ratio.

Next time you edit your portraits, crop differently than you originally envisioned, and try different aspect ratios – if you shoot digital, it’s probably 4:6 so maybe try 1:1 to give your photograph a more monumental feel. Exaggerate and crop 2:1 like the above-mentioned portrait of Stravinsky for a more cinematic feel. Other masters I would suggest you research are: Yousuf Karsh, Annie Leibovitz, and for something completely different, David Lachapelle. All have very distinct styles and have shot iconic images that you will probably immediately recognize.

Environmental is definitely my favorite type of portrait photography and whenever I have a chance to photograph my subjects this way I always jump on it. What’s great about it is that I can stick to my favorite focal length of 50mm and not distort anyone’s facial features, which becomes tricky once you start getting closer to people. Interesting fact for beginners – you can get a fast aperture (f1.8) 50mm lens for almost any camera system, maybe you even heard about the nifty fifty or fantastic plastic – these names relate to cheap versions of 50mm lenses which on APS-C sized sensors work as the portrait “favorite” 85mm, all courtesy of the crop factor.

Another great aspect of environmental portraits is that more often than not I can use available light as my main source. There is always a window or a bulb somewhere. Try placing people at various angles and distances to available light and see how their features change, how shadows and light travel over their faces and bodies.

Environmental portraits also allow the richest image in terms of placing the person in a surrounding that is somehow tied to them, and creates not only a visual background, but also tells a bit of their story. If you are, however, into strobes and meticulously lit scenes, then Joe McNally should be definitely your next stop.

Studio Portraits

Now that we’ve covered street and environmental portraits, we finally get to studio portraits. As you can already imagine, the approach for this type of photography can range from very simple and natural, to creative and complicated, but again, some ideas never change (at least until someone proves that another approach works better).

Anyway, there are few things to keep in mind that are probably even more important in a studio environment than anywhere else. Very often, it will be just you and the person you photograph, so they need to trust you, they need to see that you are confident in your actions. Even if you lose it for a moment and you don’t know what to do next or something doesn’t work, keep calm and don’t panic. Simply take a breath and let things fall into the right place again. Once you have your sitter in place, ask them to move his/her head around, up and down, into key light and away from it. Try using their hands, and look at details of their appearance that can be made the centerpiece. Eyes are the most important thing that you want in focus but that’s just another rule that sometimes needs to be broken. Draw attention to other features, exaggerate them, play with colors by using gels, maybe add offbeat props to loosen up everybody but most of all, be yourself. There are two masters of controlled environment I would like to suggest to you – both created images that you are aware of but the rest of their portfolios are equally stunning – Richard Avedon and Philippe Halsman.

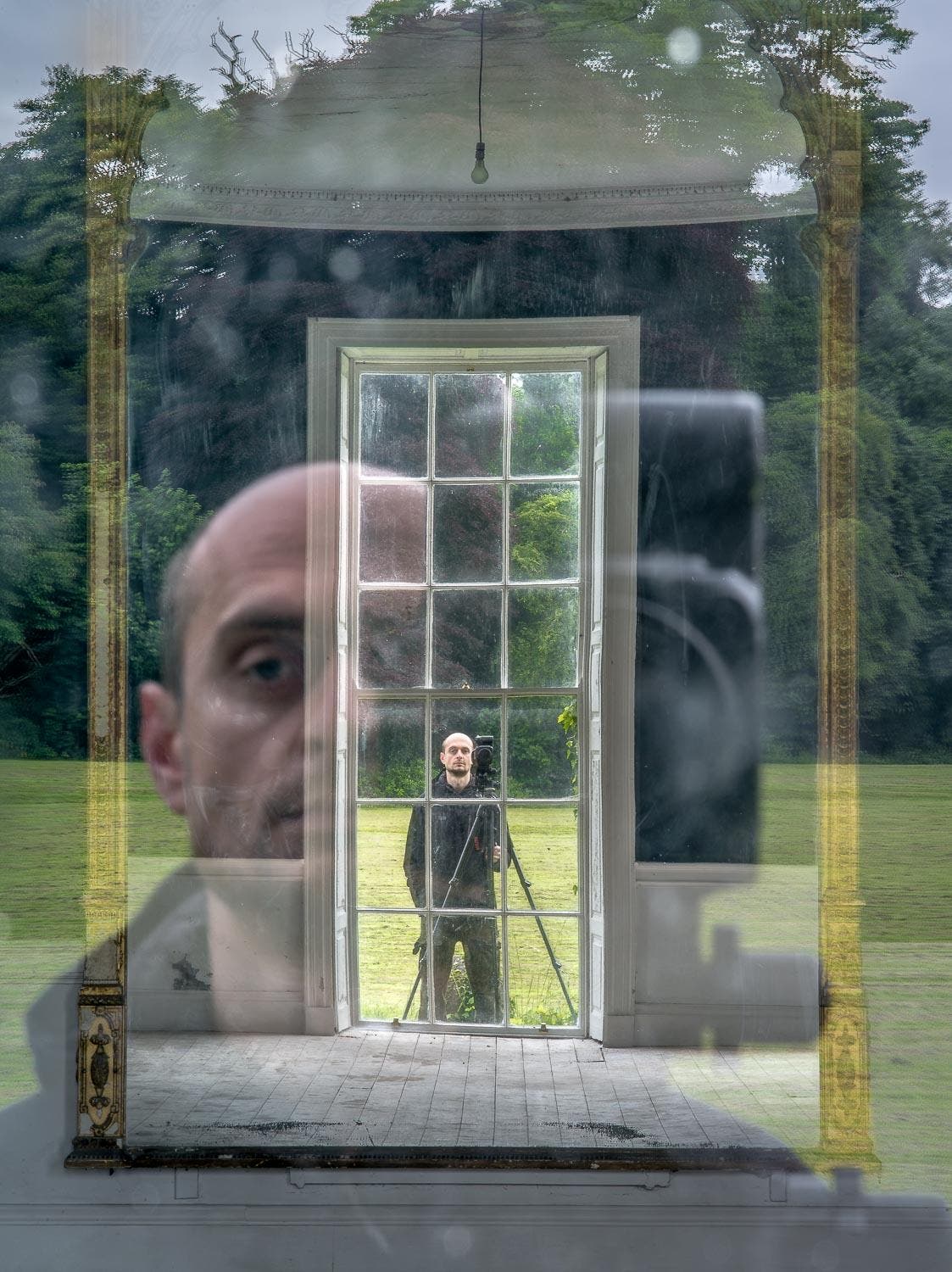

Selfie

There is one more, quite recent addition to this list – the selfie. Don’t be boring, do something else, think about reflections, interesting components, unusual angles. You are the only model that’s always available to you. (There is also a matter of headshots which are almost a separate thing altogether, and I will cover this topic in one of the upcoming episodes of “The Viewfinder”).

As with everything in photography, you can start with a very simple setup like a simple APS-C DSLR plus 50mm f/1.8 lens (for the 85mm feel). Or, maybe if you are already ahead of that, why not try something out of the box, like the Lensbaby Velvet, the Petzval 85, or investing few extra dollars in the ultimate 85mm f/1.2. There are, naturally, Ferrari’s of portrait photography, like large format cameras or the almost unreachable beasts like legendary 20×24 Polaroid Land Camera, but let’s not forget what Eve Arnold once said: “It is the photographer, not the camera, that is the instrument.” This couldn’t be more true than when creating somebody’s portrait.