It has now been a little over a week since parts of Britain voted to remove itself from the European Union. Plenty (and I mean plenty) of journalists, pundits, armchair political experts and even sometime celebrities have weighed in on the ramifications that could result from Brexit. And a lot of voices have weighed in on the responses to those responses. Everyone has an opinion. And not everyone agrees. Such is life.

There seems to be a split between those who are predicting doom and gloom and those who accuse those naysayers of being “fear mongers” and “overly dramatic.” That is, the status quo will forever continue so just keep on moving… there’s nothing to see here. When it comes to covering the U.K. film industry, the trades and film/TV related blogs have erred on the side of “doom.” Well, somewhat. While there are small attempts at uncovering a silver lining among the predictions of economic apocalypse, for the most part, everyone seems to believe that film production and distribution has been forever upended thanks to Brexit.

The Hollywood Reporter gives its two cents (or would that be pence?) by citing critically acclaimed titles like the Oscar winning “Son of Saul,” “Ida” and Ken Loach’s Palme d’Or winner “I, Daniel Blake” as recent examples benefitting from the EU MEDIA initiative. All of these titles (and more) would most likely not have been financed, distributed or even exist were it not for the U.K.’s membership with the EU. Over $180 million has gone into British productions between 2007 and 2015 and now access to that kind of funding will no longer be available once Britain takes its leave.

Not only that, in 2015 more than £1.2 million ($1.3 million) in grants were offered to British film distributors to help promote European titles in the U.K. Thirty-one foreign language movies enjoyed country-wide exposure thanks to those terms decreed by the MEDIA program. The Hollywood Reporter quotes Louisa Dent, the managing director of Curzon Artificial Eye, “not having these funds available will make distributors much more risk-averse when deciding whether to acquire a film in the first place.” She continues, “in a world where art-house films compete head-to-head against blockbusters in independent cinemas around the UK, this is dreadful news for our country’s film culture.”

CNN also managed to score this quote from Michael Ryan, chairman of the IFTA (Independent Film and TV Alliance): “As of today, we no longer know how our relationships with co-producers, financiers and distributors will work, whether new taxes will be dropped on our activities in the rest of Europe, or how production financing is going to be raised without any input from European funding agencies.” Both CNN and the Hollywood Reporter are presenting a “cutting off” scenario. Where, without the benefits derived from being an EU member, Britain will be left on its own and treated like any nation existing outside of Europe.

Variety jumped on the bandwagon by listing “Seven Likely Consequences for the British Film and TV Industry.” In addition to the issues mentioned in the Hollywood Reporter article, Variety points out how fewer UK television shows will now be picked up by the European market. Not only that, the sudden need for visa, work and equipment permits will discourage UK industry personnel to shoot outside of Britain. But here comes that possible silver lining part: a weakened pound will make it more desirable for other countries to shoot in the UK. Or maybe not. That all depends on how the devalued currency will affect the tax incentives enjoyed by major studios setting up shop in places like Shepperton or Pinewood. While on paper it certainly looks like it could be cheaper for the latest “Star Wars” or Marvel movie franchise sequel to wave their light sabers and Infinity Gauntlets on Her Majesty’s soil, the benefit of government sanctioned subsidies are more appealing from a budgetary standpoint than that of a strong U.S. dollar. And with the pound dropping in value, Britain may have to reassess whether it is financially worth it to continue with those incentives, because it may no longer be affordable to do so.

After citing a report published in The Guardian, popular film production blog No Film School reveals how only a small fraction of British films are profitable. From 2003 to 2010 only 7% of UK films saw a return for investors. But producers and distributors were willing to take those losses thanks to the EU subsidies and foreign investor-partnerships encouraged by EU membership. Now that Brexit has become a reality rather than a questionable threat, the British film industry will be shut out of the financing opportunities that also nurtured creative work. This might result in an oft-repeated mantra currently targeted at the U.S. film industry: films will become too “mainstream” and contrived to earn a buck rather than foster an atmosphere of risk taking and originality.

No Film School is also quick to point out how Brexit will affect Britain’s export activities. That last year alone, 41% of the U.K. total film output was distributed across Europe (thus surpassing American exports) thanks to the EU. Alas, that shall be no more.

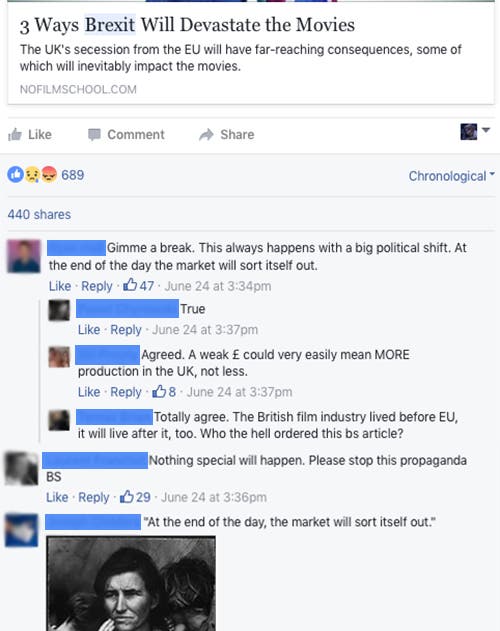

What might be more interesting than theorizing over the consequences of Brexit is the general public’s response to all of this. Rather, the British public’s response. While there exist those who were against the EU exit, there are plenty of vocal proponents out there as well. And take a look at these comments replying to the No Film School piece on its Facebook page:

This is but a mere percentage of the voices lashing out at trades like Variety, Hollywood Reporter, No Film School and anyone else who has attempted to contribute to the “let’s predict the future of Britain’s film production industry post Brexit.” But are they right? Is there really nothing to worry to about?

Another silver lining not mentioned by most of the media is how the UK will be now able to create its own rules, call its own shots and, possibly, develop its own subsidies for film in general. Britain is not an ex-EU member quite yet. Experts predict the break off will not be complete until sometime in 2017. Although there was a drop in UK stock prices immediately after the announcement, they seemed to rebound after a few days or so. There is also talk about how central banks are prepping for a new round of easing, which is an indicator of Euro-centric investor confidence.

However, the caveat rests in what the government will allow based on what it can afford… back to that devalued pound again. And as of yet there is no discernable, potential leader being mentioned to lead the UK into this new era. Should the British stick to their usual election plans, establishing a new Prime Minister will not happen until 2020. It will be a long, painful process. So while the future for UK film and television production may not be exactly bleak, it is very much uncertain.