I did not grow up loving, or really even liking, photography. My father, a photographer, was successful in his field, if not his family. My parents separated when I was born and got divorced when I was one. Photography took on the color of a troubled home.

When I was dragged to a retrospective of Richard Avedon’s or to a tiny gallery hidden in a Soho building in New York, it was mostly against my will. These were my father’s activities and passions, not mine.

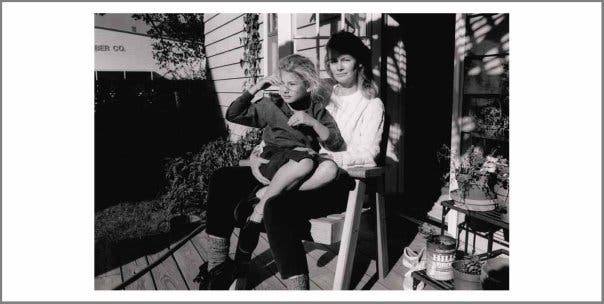

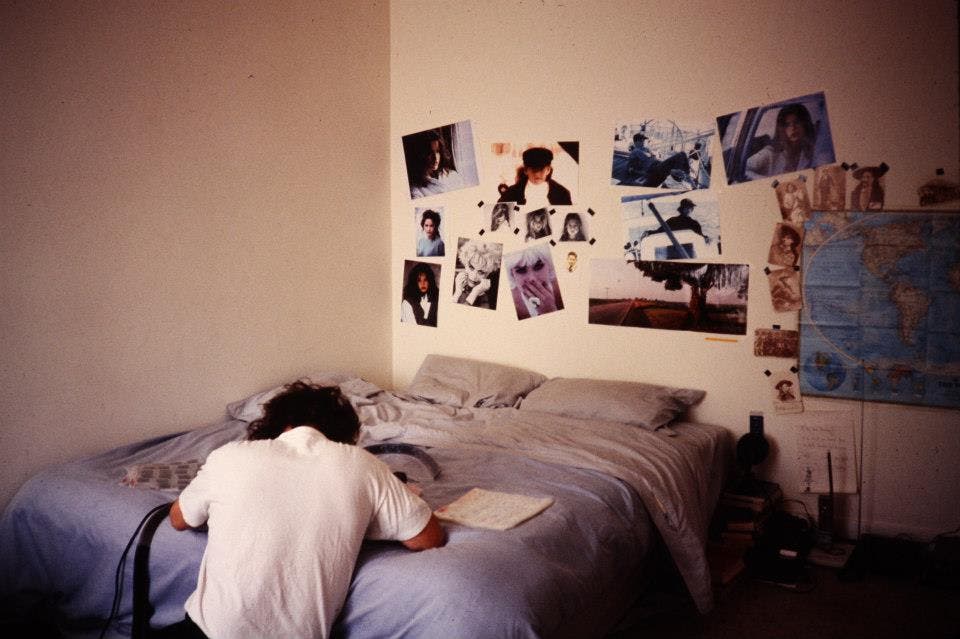

The small steady town in Iowa where my mother raised me was a far cry from the world my father inhabited. The transient walls of his New York and Paris apartments were vision boards taped with prints, maps and tear sheets from magazines like Harpers Bazaar. He lived in and for the fantasy of fashion photography, using it to manifest his sensibilities and dreams of an idealized life, regardless of how far removed from reality it struck me.

Photography to me was a lie, and a painfully personal one. It was cruel, stripped of the kindness and connection I sought from a father I felt was absent at best and woundful at worst. I disregarded it.

It wasn’t until the ripe age of 22 that I gained a new perspective. I’d only ever known SoHo and the fashion set in New York, but now I’d moved there full time and was planting roots of my own, meeting actors, artists and other creative types while calling a closet in East Village my home. I couldn’t have been happier.

I got my dream job working as a writer, producer and director for a travel TV show. I’d begun to find my way.

Working with limited budgets and resources, I knew I wanted to maximize my abilities on set and so I picked up a still camera, simply because it seemed the cheapest and most accessible way to understand the technicalities of capturing light for filmmaking. With a Canon G9, a small point and shoot camera with manual capabilities, I started to study the relationship between ISO, aperture and shutter speed.

Simultaneously I was taking undergrad night classes at the New School. In a course called The New Documentarian, my professor (the remarkable Suzanne Snider) introduced me to a form of photography I was unfamiliar with. I began to study the works of people like Dorothea Lange and Mary Ellen Mark.

The photographer Justine Kurland said, and I am paraphrasing, that every photograph tells at once both the truth and a lie. I am old enough now to recognize the subjective nature of things, that the world is comprised of shades of grey rather than black and white, truth or fiction. But when I discovered documentary photography and photojournalism, I felt I had for the first time seen something true.

What followed was a ravenous period of consumption that I spent delving into every opportunity I had to view photojournalistic work across New York City.

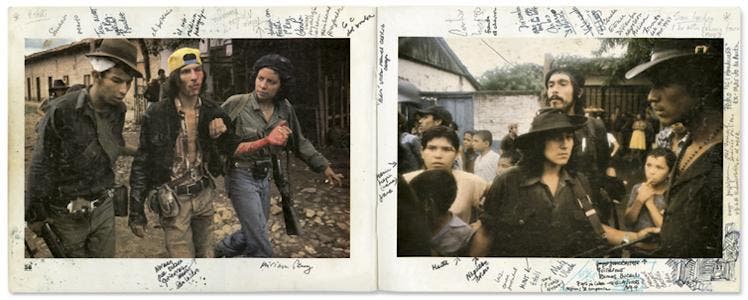

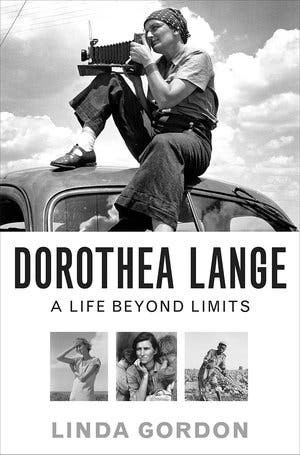

I visited the International Center of Photography gallery on my lunch breaks, where I encountered the photographs of Susan Meiselas and Sebastião Salgado. I read Witness in Our Time: Working Lives of Documentary Photographers. Dorothea Lange’s biography, A Life Beyond Limits, became my bible and blueprint for the life I wanted to live.

I saved my money and upgraded to the revolutionary and still relatively new Canon 5D and marveled at the images produced by a full frame camera. I explored new formats, taking the ridiculously heavy Mamiya RB67 on a neck strap out into the streets to shoot medium format film which I then developed in my bathroom. I was obsessed. My interests grew.

Suddenly I was rediscovering the work of Avedon, and Penn, and my father. I sought out retrospectives and SoHo galleries. I asked questions and in doing so, learned that my grandfather, who died before I was born and who I’d always heard was a banker, had enlisted as a photographer for the British military during WWII. And while I knew my paternal uncle was a successful portrait photographer in San Francisco, the significance of yet a third photographer in the family had never struck me.

That said, given my history, the last thing I expected was to marry a photographer, but then I met and fell in love with the best and kindest man I have ever known and he happened to have that job title.

Now we find ourselves blessed with a beautiful and lively baby girl. She runs, plays and dances, and doesn’t complain when we sneak photos of her, at least not yet. One of the first gifts she ever received was a plastic Fisher Price camera. The top of the camera has a square that’s supposed to represent a flash. It rotates in circles when you press the shutter button down. Round and round it goes.

Of the many things I love about our little girl is that, even though she is our daughter, she is and always has been her own person, even in utero. Photography may run in her blood but what she does with that will be her story to tell.