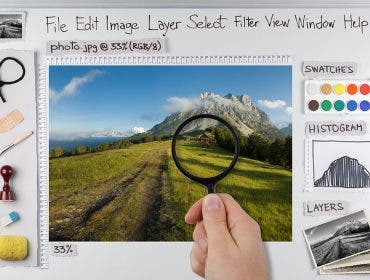

Hello. My name is Derek and I’ve been a Photoshopaholic since…

I’m not poking fun at anybody, as I’ve been fortunate that until now my addictive behaviors (Diet Coke and photography) have been relatively benign. But now I have a third addictive behavior: Adobe Photoshop. Sometimes I can’t stop “improving” my pictures. The instant feedback and endless opportunity to change them has built an irresistible neural circuit in my mind. So now I not only take pictures like a chain smoker, I tweak photos endlessly like Felix Unger trying to straighten out the housekeeping of Oscar Madison.

Oh yes, I know about Photoshop addiction. And it’s not helping my pictures. Or yours.

Here are five main offenders of overcooked Photoshop photos, and how to control our urges

1: Don’t be a super soaker saturator

Congress should pass legislation against those who super saturate. Photoshop’s saturation control is like the volume control for color, and pictures are being pumped up like everybody is deaf. Photoshoppers want their pictures to grab attention just because their color is loud. Composition weak? Just dial up the color!

Common examples of this behavior include autumn scenes erupting in never before seen brilliance, hazy blue skies dialed up until they seem to be dripping wet paint, sunsets sizzling with sci-fi scintillation, and clothing, fruits, and lawns all bursting with psychodelic color.

Just ducky? These bathtub companions are soaking in blinding color.

Unretouched orignal shows these squishy little guys in all their natural, rubberized glory.

The cure

The next time you open the saturation function in Photoshop, pretend you’re in the library and ask your colors to whisper. Don’t not shout and scream: “I’m the brightest green ever” or “Have you ever seen an apple redder than me”.

Instead of increasing saturation of the entire picture, do it selectively. Either by choosing a color in the saturation function or by first selecting the area (with a feather of a couple of pixels) you’d like more intense color and apply it just there—but lightly so it doesn’t look artificial.

Fine-tune color saturation by only saturating selected colors.

Soon, you’ll enjoy the natural world more and begin to accept its colors as they are; you may also that with less intense saturation that you can get good looking prints on the first try. Maybe you’ll even shift your attention to composition, subject selection, or time of day to really improve your photos.

2: Cornering Curves and leveling Levels

Curves and Levels are the perhaps the most basic Photoshop adjustments because they address image fundamentals: brightness, contrast, and color.

Marching in the same noisy parade as super saturated colors is eye-popping contrast. With the Levels and Curves function, it’s easy to goose the contrast but the result is like gunning your Porsche down a suburban street—you’re likely to be pulled over or gain a bad rep with the neighbors as a reckless show-off.

Good action shot, lots of details. But do most people leave well enough alone? Noooo….

Overdoing levels=too much detail lost in highlights and shadows

Being heavy-handed with Curves and Levels can crash your picture. Boosting contrast risks squashing both highlight and shadow details. In case we’re not clear about what contrast is it’s the tonal range of brightness in a picture—from the shadows to the details. It’s usually considered good to have as many tonal steps as possible. And while revealing both a distinct, detail-less black and white gives the picture a nice shine, don’t sacrifice important details.

When you boost overall contrast, you squeeze together the dark tones, the medium tones, and the light tones. In short, you reduce the number of distinct, individual tones. At first glance, especially on a monitor, the picture may seem to jump off the screen. But squeezing together tones is another way of saying you eliminate them and some of the detail they held. Like removing keys from the piano, it lessens the breadth of nuance possible.

Overdo the contrast or brightness adjustments and you can say good-bye to the individual bricks in that sunlit lighthouse and to the subtle gradations in those fair-weather cumulus clouds. Wave so long to the hairs on your black cat; watch the curls on or your girlfriend’s black hair merge into a shapeless mass. Even a blue sky, which seems to be a uniform blue, actually consists of a wide but subtle range of tones as it reaches from the horizon to zenith. But if harshly adjusted it may seem like an artificial spill of blue paint across the top of the picture.

Long considered the vanguard in the art of photography, expert black-and-white photographers prided themselves on achieving the widest range of tones possible from the shadows to the highlights. So should you.

So the next time you open up the Curves or Levels function, take the gentle approach. Add a bit of snap by darkening shadows that hold no worthwhile detail and whitening that white wall but don’t sacrifice the lace on a bride’s dress or the buttons on the groom’s tux.

3: Should grandma’s face be as smooth as a baby’s?

When you start making your grandmother’s face as smooth as the bottom of her newest great grandchild, you know you’ve got a problem. Yeah, most of you don’t go that far. But how far do you go? If you haul out the Healing Brush and clone tools and make her look as good as your wife unretouched, or retouch your wife to look as good as your twenty-something daughter, you’re going too far.

Don’t give grandma a makeover!

Retouching is great. Photographers have retouched portraits since the mid-1800s and artists have idealized their sitters long before da Vinci lifted Mona Lisa’s lip (do you really think she looked like that?).

She earned her wrinkles–leave ‘em alone.

Although Oprah Winfrey and Barbara Walters expect their youthfulness to be reavealed on magazine covers how far should you retouch the faces of your family? It’s a tricky question. And not to be sexist but those who inhabit the world of makeup do tend (but not always) to have higher expectations about how their faces appear. But at the same time, with Photoshop at your disposal, it’s quite easy to make those portraits you shot yesterday appears as if they were taken few decades ago. The problem? One, you’re dissing reality and truthfulness, albeit seemingly harmless. But maybe not so harmless if the owner of the face mentally compares the portrait seen in the picture to that seen in the mirror. What then?

So by all means, soften the wrinkles with a light Gaussian blur with a radius setting of a pixel or two but don’t sand blast them with a double digit radius setting. Remove some crow’s feet from the eyes, remove the worst of the age spots and blemishes and the distracting strands of hair. But don’t turn a wonderfully imperfect person into an ideal that can’t be achieved or–worse yet–will barely seem recognizable.

4: Sharpen to show—not kill

Sharpening photos is easy to overdo—especially for web display. Oversharpened photos seem filled with razor-sharped edges and internal details that look as prickly as a bed of nails. And tiny halos appear on contrasty edges. An oversharpened photo looks unnatural.

For general overall picture sharpening you can avoid most sharpening artifacts by not exceeding these settings:

Size Radius Amount

web photos 0.4 to 0.8 60 to 100%.

Printed photos 5 x 7 to 8 x 100 0.8 to 1.5 100 to 150%

Sharpening gone wild: too much sharpening can lead to halos on the edges

The table at the end of this tip gives more general sharpening guidelines by subject.

More important than such broad recommendations is your approach to sharpening.

Let’s assume you have a correctly exposed photo that is “sharp” out of the camera—that’s to say there is little if any blur from camera or subject movement.

So let’s consider four criteria when sharpening:

• The subject

• File size

• Type of output (monitor or print)

• The important content within a picture

Sharpen selectively and subtly for a more natural look.

This selective sharpening looks more natural, doesn’t it?

Type of subject

Sharpen soft and gentle subjects less. Some flowers, dreamy landscapes, portraits of babies and often women get minimal or selective (eyes and teeth, maybe hair) sharpening (sometimes you’ll even lightly blur parts or all of them). Scenes that may look good with a bit of oversharpening include high action sports like soccer, brightly lit rocky landscapes, close-ups of a butterfly or hummingbird. The point is to customize your sharpening to make it appropriate for your subject and the mood you’re conveying.

Size of the file

Large files require more sharpening than small files. Typically you would increase the radius setting as the file size increases. So if you’re making a 16 x 20 print, you may set the radius to 2 or 3 and the amount to 200%. If you’re making a 4 x 6-inch print, then a radius of 0.8 and an amount of 100% (or slightly less) may serve you better.

The type of output

Monitors have lower resolution than printers. You need to use lower sharpening for monitor/web display than for a print. At the same time, because the monitor’s resolution is lower than a print, it’s more difficult to determine appropriate image sharpness for a print by looking at the photo on the monitor (where it will look sharper than it does in the print). When you’re adjusting an image for print, it should look a bit ovesharpened on the monitor.

The area within a picture

Here’s the most important tip. Sharpen important areas within a picture selectively (or blur them selectively). If you’ve frozen a wake-jumping waverunner in mid-air, you might lightly sharpen the whole picture, but then select the wave runner (use a feather of a pixel or two) and give it extra sharpening—but don’t overdo it or it will look pasted into the scene. Similarly, sharpen the butterfly and flower and not the background, in a portrait sharpen the eyes an extra touch. If you variably sharpen several areas in a picture use similar settings so you don’t make your technique call attention to itself.

Unsharp mask settings (A=amount, R=radius, T=threshold)

Subject Print Web

General snapshot A-125%, R-1,T-2 A-80%, R-0.7, T-2

Detailed content A-150%, R-1.5, T-1 A-100%, R-0.8, T-1

Action/sports A-175%, R-2, T-0 A-100%, R-0.8, T-0

Female portrait A-80%, R-0.8, T-8 A-40%, R-0.3, T-6

Moody, dreamy content A-60%, R-0.5, T-4 A-60%, R-0.3, T-4

It’s an imperfect world. Accept it.

Organic and natural. Foods that grow without the artificial interference of inorganic chemicals. That’s the trend in food. The reason? Bcause natural is, well, natural. Therefore, it must be wholesome and healthful. It’s what nature has given us for thousands of years.

However, the trend in Photoshop philosophy seems to be the opposite. Too many photos seem artificial, almost unreal, they stray too far from the original scene. It’s as if a musical group trying to make up for some shortcoming in talent simply turned up the volume. Or a chef poured in the sugar or spices and overwhelmed the natural flavors of the meal.

Perhaps most disturbing is the psychological motivation behind this. It’s as if many of us are dissatisfied with both the world around us and our photos of it. Instead of trying to appreciate the subtleties presented us we have to amplify all the traits of picture and turn it into that loudmouth, blustering salesman who sells us not on product quality but by overpowering force.

Let’s treat our pictures, especially those of natural things, more kindly and gently so as to preserve the natural beauty of our subjects and harmonize our minds with the world as it is. We will not Hollywood our portraits, tourism bureau our landscapes, or supermarketize our apples and strawberries.

We will celebrate the world around us for the way it is (well almost the way it is) and accept more of life’s flaws and imperfections, because that’s the way life is. Since we are imperfect ourselves, accepting the imperfection around us may make us better people—and better photographers.