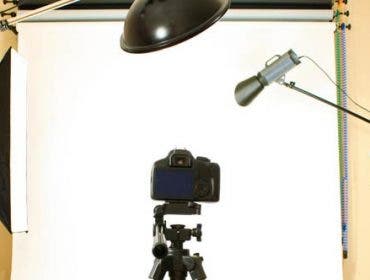

Photo: Matěj Šmucr

Between planning shoots, post-processing, and meeting with clients, copyright may feel like an afterthought for many photographers. Even if your work has never been misappropriated in the past, most professional photographers must deal with copyright issues at one point or another.

These five copyright principles can help you better understand what rights you have in your work and addresses a number of common copyright myths.

Photo: Daniel Foster

1. Copyright is automatic almost everywhere in the world.

Both U.S. copyright law and the Berne Convention award copyright to a creator the moment a work is expressed in a “fixed” medium.

So once you click the shutter, the copyright for the photograph is yours. The length of copyright depends on the country. In the US, it lasts for life plus 70 years, while in Germany it lasts for 50 years since the latest date of publication.

Photo: Daniel Foster

2. US Copyright Office registration is not necessary but advised.

You don’t need to register your work to own the copyright. However, should a dispute occur, copyright registration provides a number of unique benefits– most notably presumed validity of your copyright ownership and the ability to collect up to $150,000 in statutory damages.

Only registrations made through the U.S. Copyright Office are valid. One of the most dangerous and enduring copyright myths out there is the idea of a “Poor Man’s Copyright.” Many mistakenly believe that you can simply mail yourself a copy of your work, keep the envelope sealed, and use the postmarked envelope as proof of creation and ownership. It’s not a legally valid method of registration. After all, anyone can put a photo in a fancy envelope.

3. You don’t need to display a copyright notice or watermark on the photo to own the copyright.

Since March 1, 1989, the use of copyright notice is no longer required under U.S. law. You can of course display it as a reminder. The same applies to watermarking. Both are useful for preventing theft, but there are a number of reasons why it’s not always practical to display them, and there is no requirement to do so.

4. Don’t fall for “fair use” myths.

Fair use is an affirmative defense to copyright infringement that provides exceptions to artists’ exclusive rights for limited educational use, parody, commentary and other purposes.

Fair use only applies in a limited number of situations. Many image users and photographers mistakenly believe that fair use covers any educational or editorial use, for example. Crediting the photographer, making small edits to a work, or using a work in a not-for-profit context do not in themselves fall under the fair use canopy.

Virginia Tech has published an excellent fair use analysis tool for guidance in determining if a use of a work could qualify as fair use.

5. Avoid transferring the copyright to clients.

We’ve heard an increasing number of stories of photography contracts containing copyright transfer clauses. There are very few situations where you should transfer copyright to a client– by doing so you give all rights a photo, even the ability to display it in your portfolio. Most importantly, you give up all future licensing income for that photo.

When clients ask for a “transfer of copyright,” they’re often just looking for the right to use a work and possibly for a successor to use the work if the company is ever sold. A contract should ideally spell out exactly what type of use is allowed with no provision for an exclusive license unless the client provides additional compensation. Keep in mind that some of the contract clauses may limit your rights just as badly as a transfer of copyright.

Like everything else in life, a little bit of copyright knowledge and careful attention goes a long way in preventing mishaps. Copyright is always yours unless you expressly give it away, and it’s a right you should protect. After all, what’s the point of shooting it if you don’t own it?

This post is written by Pixsy, online platform that helps photographers find and fight image theft. You can sign-up here or follow them on Facebook here.