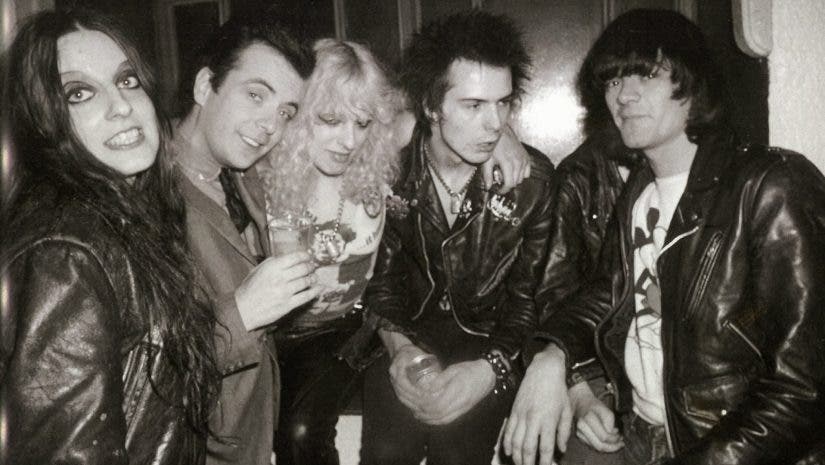

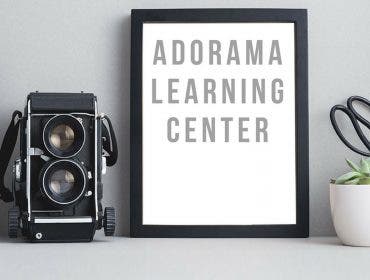

When I first met Danny, it was by way of introduction through a journalist friend of mine. And I was, admittedly, star struck. This was a man who worked with The Doors, had managed Iggy Pop, had toured with The Ramones and was friends and acquaintances with so many icons and rebels of the time. And yet here he was graciously cleaning his kitchen table because he wanted his guests to feel comfortable. The man actually made me tea! Danny Fields… makes tea. All this while surrounded by photographs either taken by him or featuring Danny hanging out with Bowie, David Johansen, Patti Smith, etc. You think back on rock history? You might think of Max’s Kansas City. And Danny was there frequently. The proof is in the photographs on his wall.

The 70s were a particularly catalytic era for popular music. While Rock n’ Roll had in its inception the blues and folk parlors of Greenwich Village and the American south, the various sub-genres came to be during the turn of the 1960s leading into the next decade. Stadium Rock, Heavy Metal, Folk and Country, Disco and ultimately Punk would grace the covers of music magazines when, prior to that, ad space and columns were limited to Elvis Presley, Frank Sinatra and the occasional Motown single. Bands like the Beatles and the Rolling Stones had already started to mix things up in the mid-to-late 60s, while underground acts like the MC5 and Velvet Underground were enjoyed by a specific audience. But it was the 70s, where all of these differing sounds came to the fore; a rambunctious Led Zeppelin would grace a magazine cover one week, then the more tranquil James Taylor would headline the next.

Most people reading this article listened to or were fans of these bands during their formative years. When we think of the 70s, we reminisce over how we listened to Bad Company, thanks to a cousin’s 8-track system in his car, or were turned on to the New York Dolls because you had that one friend who wasn’t afraid to wear eyeliner, having suddenly gotten into glam rock like David Bowie, Gary Moore and T-Rex. Or how a song like Queen’s “We Are the Champions” has forever remained embedded within our psyche thanks to sports championships and popular broadcasts.

We always remember the artists. We always remember Disco. We remember the cover art of an album and a favorite tune. And yet, for those of us who are true fans of the history of popular music, other names are spoken within the same breath while mentioning such talents as Neil Young and The Runaways. These are the “non-artists” who, in their own way, were artists of a sort. The personalities who completed the scene by just being there writing, promoting, even managing, and therefore, influencing the direction of music at the time. Names like Lester Bangs, the celebrity music journalist immortalized by Philip Seymour Hoffman’s performance in the film “Almost Famous.” Bill Graham, music impresario and ruler of the venues the Fillmore East and West. The future Mrs. Paul McCartney, Linda Eastman, who thanks to her status as the girlfriend of a Beatle, had unprecedented behind-the-scenes access.

And then there is Danny Fields. Unlike, say, a Hilly Kristal, who built a venue called CBGB’s that would introduce the world to the next phase of influential performers because they came to him, Danny found himself in the right place at the right time – much like a Forrest Gump or a Zelig who were present at key moments in world history and wound up affecting the direction in sometimes unintentional ways. But Danny is no “Gump.” He is a wry, canny, intellectual talent who easily transitioned from music journalist to public relations to band manager and back again. He was, simply, an affecter of change; while the Ramones are credited as the catalyst for the punk movement it was Danny Fields who brought them to the public eye. While a lot of controversy has surrounded the now legendary comments by John Lennon with regard to the Beatles being possibly more popular than the son of Christ, it was Danny Fields who published that interview for the American press, which resulted in a nation-wide incendiary response.

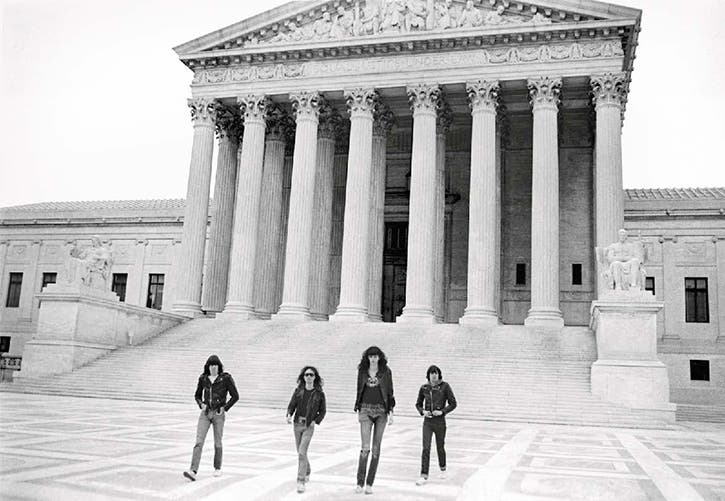

Danny is polite but to the point. Blunt but without a shred of ego. There is that contradictory aspect of his personality where you feel he knows he is smarter than you and yet he is the sweetest guy you could ever meet. Not that he has not earned that ego; Danny has outlived most of his contemporaries and survives as a testament to his creative savvy and the scene he played an instrumental part in. And it appears he might be entering into the next phase of some notoriety. The Queens Museum is currently exhibiting images and paraphernalia celebrating The Ramones. Titled “Hi Ho, Let’s Go! ” Danny’s photographs are featured among many other artists. “My Ramones,” to be published by First Third Books, will be comprised entirely of Danny’s photographs of the Ramones during the ’76 -’77 period he managed the band. Danny will also be a featured speaker at the year-long, 40th-anniversary celebration of punk music sponsored by punk.london.com. And, finally, he is the subject of a new documentary that is already receiving strong buzz on the festival circuit.

“Maybe somebody might make a terrible mistake or there would be a fight or something but you’d see it later or hear about it. But there was no reason to watch it. So it was best to stay at home, get into a car and go to the parties. That’s what we thought of the Grammys.”

But Danny is quick to point out that he is just a participant in the projects listed above. He didn’t make the documentary. He is just in it. He didn’t publish his upcoming book. His images just happen to be in it. And as for the Queens Museum exhibit, his part is a mere percentage of what is presented there. In fact, Danny would prefer to look back on his history with the Grammy’s rather than speak to his involvement in “Hey Ho, Let’s Go!” Apparently, the Grammys are co-sponsoring the event. Or, rather, it could be construed as a “Grammy’s Exhibit.”

“What exactly would be a Grammys exhibit?” Danny exclaims. “The Grammys is a TV show. That’s it. In the 70s during the heyday of the Grammys when they meant something… they were important… they were so big, five or six record companies would each throw unbelievable lavish parties – some would get an entire floor of the Four Seasons restaurant – and a record company would send me a limousine just because I was in the press then. Just to get me from one party to another. So the Grammys meant something then but… what we all did was we’d start getting dressed or taking our showers just before the telecast started and then we’d send for our cars and then go to the parties. Because who gave a sh–? You know? Because who cared about what happened? Maybe somebody might make a terrible mistake or there would be a fight or something but you’d see it later or hear about it. But there was no reason to watch it. So it was best to stay at home, get into a car and go to the parties. That’s what we thought of the Grammys. It was a job involving a show that you’d miss and then you’d go to the parties afterward. Why are we talking about the Grammys anyway?”

I remind Danny that he brought up the subject in relation to the Ramones exhibit at the Queens Museum. “This show in Queens wouldn’t exist without the Grammy money. By the way, it would have been humiliating for the Ramones to even have been on the Grammys because of the quality of the artists each year. It was like death by Grammy. They got space in the Grammy museum because they’re all dead.”

“Paul McCartney decries racism in America and calls it ‘a lousy country,’ I thought, ‘Whoah! There’s a cover line for my teenage magazine! Bet they’ve never seen anything like that!’ And then John Lennon says, ‘I don’t know which will go first: Rock n’ Roll or Christianity?’ And I go ‘Whoah! There’s another one!’”

Another Queens native, Danny Fields was born Daniel Feinberg in 1939. He was accepted to the University of Pennsylvania at the very young age of 15 then transferred to Harvard Law School… only to drop out a year later. I ask Danny how he got into music journalism in the first place.

“I was fiddling around with print, editorial publications, magazines etcetera,” Danny responds. “And there was an ad in the Times for a manager of a pop magazine. I thought it was pop art. So I went for the interview and found out it was for a pop music magazine. So I bought a copy of Billboard. And memorized it. And went back for the follow-up interview. That’s how I got the job at Datebook. They put out a magazine that was essentially in competition with 16 Magazine for a young, female teenage demographic. And that was not what I wanted to be. That was not my taste in music, to put it mildly. So I started slipping things in like Jefferson Airplane and The Byrds and the Rolling Stones.”

I bring up the infamous John Lennon quote. Danny elaborates, “I did cause a little trouble because the publisher had bought interviews with John Lennon and Paul McCartney that had run in London about eight months earlier. Paul McCartney decried racism in America, saying “it’s a lousy country’ I thought, ‘Whoah! There’s a cover line for my teenage magazine! Bet they’ve never seen anything like that!’ And then John Lennon says, ‘I don’t know which will go first: Rock n’ Roll or Christianity?’ And I go ‘Whoah! There’s another one!’ Bear in mind these stories had run a year prior in London. And it’s 1966. So it was quite an outrage here. The Beatles had death threats. And the Klu Klux Clan rallied in the parking lot of the stadium in Memphis.”

Although he got a lot of heat for publishing that interview, Danny reveals he was fired from his position for an altogether different reason. He concedes that at the time he didn’t know how to be an editor, “you can’t wait until someone comes to town so you can interview them. So you would make up stories.” So he was already on his way out before that infamous controversy broke with regard to the Beatles. However, he wanted to place Lennon’s comments in their proper context, “Poor John Lennon. They had to take him off the tour and send him to Chicago. It was the only place they could get enough cable connections or something. To hold an international press conference with him, to be called upon to defend why he said they were more popular than this Jesus person. And he didn’t understand why. Like ‘why are they asking me about… this was published over a year ago!’ But, yeah, they stopped touring after that. It wasn’t the only factor. But I’m sure no one likes dealing with Klu Klux Klan rallies as they’re on tour.”

Prior to working for Datebook, Danny mentions an earlier role at a magazine called Liquor Store Monthly. I exclaim, “Liquor Store Monthly?! What was that all about?”

Danny: “If you had a new bottle shape for your gin, or a new kind of vodka, you would buy an ad. It’s a trade magazine. The owner was a big hunter-fisher. An old-fashioned Republican. And he used to hunt and fish all weekend and bring in the chopped up animal parts wrapped in a freezer that I carried on my back to the advertising agencies whose asses he was kissing to get advertisements for his magazine.”

“Someone who writes for a magazine could also be a consultant for some record company in Brooklyn and book a club at the same time. So I would say your modern youth is an example of that. More so. In other words, there are no lines to blur.”

Moving on from enticing ad execs with raw meat to covering the Beatles for Datebook Magazine, I then ask Danny if he was a part of a discernable music scene prior to being a music journalist. Or was it the journalism that introduced him to the scene?

“I had nothing to do with the music scene. I had just dropped out of Harvard Law School and moved back to New York. And was futzing around for something to do,” explains Danny. “I got a masters degree – I think, I’m not sure I ever got the piece of paper – at NYU and lived in a funky hotel. Then I went to California for the summer and then I came back. I got a job at Hulabaloo, which become Circus Magazine. So I was there for a few months. And then I got hired by (record label) Elektra in ’67 and they needed a publicity department. So I created a publicity department. I began working a week just before ‘Light My Fire’ became number one. It had suddenly gone from a cool record company with Paul Butterfield and Judy Collins and stuff to having a number one ‘career single’ from a really hot band called The Doors.”

I then ask Danny how he made the transition from being a music journalist to working in PR. Or whether that transition presented any challenges? “It was the same thing. Where was it different? There’s no difference. It’s people floating around in a chunk of the media universe which itself is floating around and at certain levels they crisscross all of the time. Executives, the publicists, the writers become presidents of record companies.”

My response, “Is that something that would happen now? Seems like there is a separation between those who write about music in general and the producers and those who sell the music.”

Danny: “I would say there is less demarcation now. Someone who writes for a magazine could also be a consultant for some record company in Brooklyn and book a club at the same time. So I would say your modern youth is an example of that. More so. In other words, there are no lines to blur.” Danny then adds, “you have to find that one thing you love. Maybe 1.75 things you love that bring you in. For me it’s always been the songs. I could be at a record company because I was writing about artists at Elektra that I liked like Tim Buckley and The Doors. And then the record company hired me. So it didn’t seem like a huge difference.”

But then Danny pauses to reflect a bit. “But maybe you’re right? Back then we had to help present, promote, whatever you like. The publicity departments, the artist relations departments – which meant a lot to artists but not too corporate – they were the first to go when the record industry deflated during the days of Napster. Because records were not a viable revenue stream anymore. Who bought records?”

I ask Danny how his photography came into play. Was it something he was always involved with? Did he ever consider himself a “professional?” “I’m an amateur,” he says. “I am not a professional photographer. I never have been. My dad came back from the war with this camera. Something we always called the ‘Russian Leica.’ Before Germany turned on Russia in the days of the German-Soviet Nonaggression Pact, they were sharing technology. So they sent Leica technology to Russia. So that was a precious item. When I got permission to look at this, you know, hold it, I got to dismantle the lens, clean it – it was dirty! And I got so excited about that, I was reading about lenses and Leicas and became obsessed – still am – with owning a Leica. But I never did.”

“Around 2004, I was at the opening party for a show called ‘Bande á part (an exhibit in Paris on NY photographers).’ I was very proud to have a bunch of pictures in there. Well, at the opening night party I squashed my 35mm camera. And that was kind of the end of… I just went digital from that point on.”

So what did you wind up owning, Danny? He answers, “I think in the early 70s I got a Canon F1 and that was the beginning of my 35mm. But I took pictures all along and my father had a darkroom in our house and I used that and I was enlarging pictures from negatives so I was always a hobbyist amateur photographer.” Does he miss film, what with the digitization of photography? “It occurred to me when we were at the edge of digital and film, assuming that you didn’t have a major laboratory picking up the work for the magazine you were working for, you know, the processing, the cost of the film, whatever… Around 2004, I was at the opening party for a show called ‘Bande á part (an exhibit in Paris on NY photographers).’ I was very proud to have a bunch of pictures in there. Well, at the opening night party I squashed my 35mm camera. And that was kind of the end of… I just went digital from that point on.”

Danny prefers using a point and shoot because he likes to take what he calls “ambush pictures.” But he still dreams of owning a Leica, “I knew all their lenses but I never owned one. All I had was daddy’s Russian Leica. Then my brother had it and I think he lost it in a fire.”

Getting back to his role in the music industry, I bring up a band that’s somewhat synonymous with Danny’s identity, the Ramones. “Were the Ramones the first band you decided to manage?”

Danny: “No, no. I kinda’ managed Iggy Pop after the Stooges were dropped from their label. And I sort of stood in for the MC5 with John Landau after their manager John Sinclair went to jail. I was at 16 Magazine. But my little hobby job was writing a weekly column for the Soho News – which was an alternative to the Village Voice. Kind of. So my personal taste was pretty much part of it. I was free to write whatever I wanted. And wrote about music. For example, I really loved Television.” He continues, “The Ramones were clearly upset that they weren’t getting into the column. I meant something to them because they met each other because of the Stooges. They were the only four people in a high school of four thousand that were fans of the Stooges. And here I am, I worked for 16 and write this column and Tommy Ramone just wouldn’t stop. It was always Tommy on the phone, etc. They viewed me as this person who writes for the Soho News, who also discovered the Stooges and the MC5, and also happens to be the editor of 16 Magazine where the Ramones are so ‘why can’t we be the Bay City Rollers?’ The Bay City Rollers wanted to be the Ramones and the Ramones wanted to be the Bay City Rollers!”

I note my amusement at the contrast of two completely different bands. The Ramones were punk prototypes whereas the Bay City Rockers were tailor made for the teen market, with Danny existing as the connector between the two. “I worked, in a way, for both of them. They were both projects in my life. So I went to see the Ramones and I loved them. So they say ‘do you like us well enough to be in your column?’ And I say ‘more than that I want to be your manager.’ It sounds like a script. But it’s true. But they were so perfect I knew they would be trouble. Because the world was so mediocre and rock n’ roll was so pathetic except for, you know, Television and a very few other bands.”

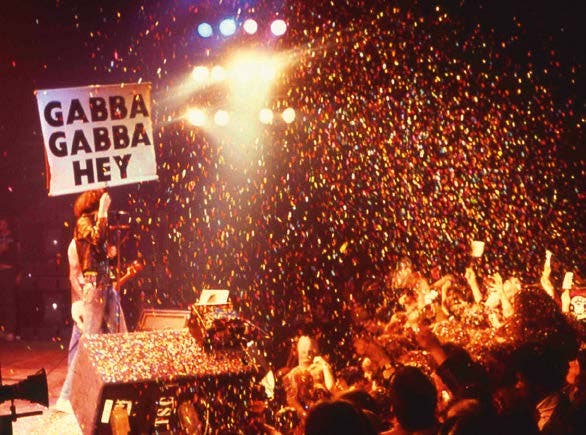

Danny then helped to sign the Ramones with Sire Records and thus their first album was launched. Danny veers into a related tangent, the current, year-long celebration of the 40th anniversary of Punk in the UK. Music historians posit that the British Punk movement can be traced back to 1976, thanks to the Ramones introduction to the scene at the time. “This whole year is the year of punk.london.com. Every day there is an event celebrating the punkiness of London. But the pivotal date is July 4th, 1976. This was when the Ramones played two shows in London that weekend. Supposedly this created a great change in the British music universe, which I now have to go to London to talk about. I wasn’t there before and I wasn’t there after. But apparently they made history. But the British Library is flying me over to talk about the Ramones that weekend.”

Speaking of the Ramones (and Danny’s photography), First Third Books is publishing a collection of Danny’s imagestitled “My Ramones.” Danny explains, “the publishers do limited editions of visual music books. They did a Marc Almond book, they did a Genesis P-Orridge book. They did a book on photographs by Sheila Rock called ‘Punk+,’ which are photographs from the early-middle 70s in England. She was married to Mick Rock. Great, great pictures. The editor/publisher Fabrice Couillerot, who is in Paris, he’s been a friend of mine for while because he’s obsessed with all things American and underground American stuff. He started his publishing company with a partner in London, Richie Franklin. And they publish high-quality photo books.”

That last sentence amuses Danny. “This is a funny side bar: they were doing a promotional postcard for their book. They called it a ‘high-quality publication.’ I said to them ‘no, you cannot use an adjective in your own promotion. Because who is going to believe you? It sounds boastful. If somebody else says it, you can use it.’ Fabrice says, ‘but it ishigh quality. I see each page as it comes off the press—‘ ‘yes, yes but you cannot boast in an ad for a book, period! Adjectives are always tricky; stay away from them.’” Danny laughs, “All you need is a quote from a review. I don’t care if you have to scratch someone else’s back. That very day, the curator of an export-import photo gallery – a photo gallery of very excellent stuff – I showed him the pdf of the book. He says ‘Oh! Who’s publishing it?’ And I say ‘First Third Books.’ And he says ‘Oh my god, they publish such high-quality stuff! What high quality photo books featuring music people!’ And I said ‘Hold on! We’ll tape that!’ So I texted London and Paris at once and said ‘I got a quote for you from an owner of a reputable art gallery.’”

“Nothing against Marky, I’m sure he was a wonderful drummer… but ‘My Ramones’ does not signify ownership, how could it? This is about the Ramones that I knew. Plus I wasn’t taking too many pictures of the Ramones once Tommy left the band.”

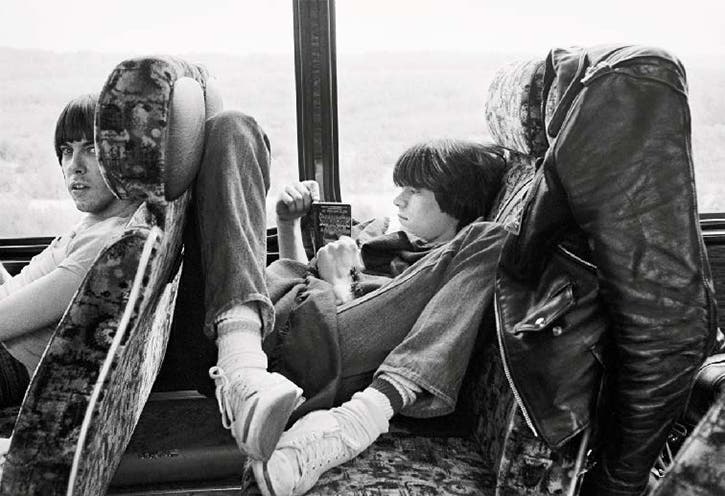

Most of the pictures involving the Ramones where taken from 1976 through ‘77. “Tommy Ramone left the band in ’77. He was the first person I ever spoke to from the band.” Tommy Ramone – whose real name was Tommy Erdelyi – was initially positioned to be the band’s drummer and manager. “When he left and was replaced by Marky Ramone, they weren’t the same to me,” Danny opines. “Nothing against Marky, I’m sure he was a wonderful drummer… but ‘My Ramones’ does not signify ownership, how could it? This is about the Ramones that I knew. Plus I wasn’t taking too many pictures of the Ramones once Tommy left the band.”

I ask Danny if he could verify a story surrounding a specific gig in Marseilles, France. Supposedly, right after the Ramones plugged in their instruments for a sound check prior to that evening’s performance, they blew out the power grid of the entire city. “That’s what we heard,” says Danny. “A large chunk of central Marseilles had a black out. They fixed it. I don’t think it closed hospitals or people on iron lungs died or anything like that. But it lasted long enough there was no time to do a sound check and a proper show.” Danny laughs, “they blew out the power of Marseilles: the second biggest city in France.”

It is an amusing anecdote. But Danny wanted to reaffirm, “I think these photos are so special because I had such close access to the band. We were both working. I mean, the manager’s work is done before the band goes on the road. There are road managers and travel agents and booking agents. But when the photographer is also your manager, the Ramones could be confident that any picture showing someone with a piece of spaghetti hanging out of their mouth would never be released to the press. But I was, like, let’s have fun with it. And they were natural at it. Still, in the dressing room when there’s five of us and I’m taking pictures of them sitting and thinking, there is not anybody else who could’ve done that. Not a photographer from an important magazine, because they would not have been sitting there casually checking out their fingernails or looking at their teeth in the mirror. That closeness to them is what the book is about.”

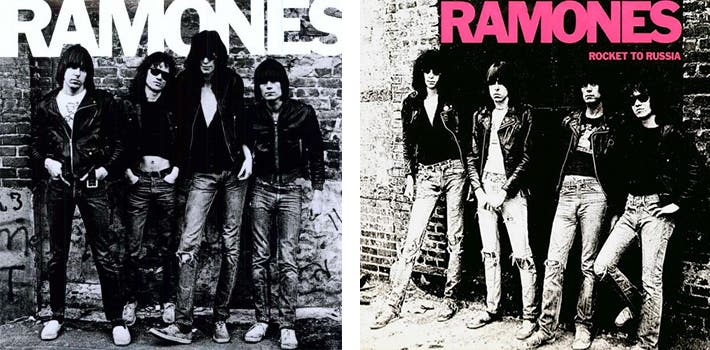

I ask him if he did the photography for any album covers. Danny responds, “I did get to do one album: ‘Rocket To Russia,’ which was an homage to Roberta Bailey’s first cover. That first cover, from the album called ‘Ramones,’ I heard that people pulled that album out of the bins because these guys looked so cool and that picture looked so cool. Something about it looked so cool. Then their second album, they hired some fashion guy and it was just awful. So for the third album I wanted to…” Danny digresses a bit, “you see this is the way you can be a publicist and a manager or a publicist and a photographer but neither but both. So I say ‘we gotta’ go back to that brick wall like Roberta’s first cover’ which established the brand, the image visually. I mean it was perfect. So we went looking for another brick wall in the East Village – the original one was no longer there. And the logo, I said let’s have it in hot pink. But Warner Bros refused to go for the extra hit of ink (which would result in five color printing as opposed to four). They were not going to go for the extra expense and I had a tantrum and so they finally did. So thank god. And while the setting and pose is similar to Roberta’s album, the Ramones name is now in hot pink which has become ‘Punk Pink.’ If you look at the London.punk.com you’ll see a lot of use of hot pink.”

Danny mentioned how he also photographed the cover for recording artist Steve Forbert (another act Danny managed) and I asked him if those were the only albums he photographed. “Oh yeah. I mean I wasn’t a professional photographer!” So I argue “but Henry Diltz wasn’t a professional photographer! Not at first.” Danny argued back, “I always thought of him as a professional photographer, he did all those albums.” So I inform Danny of how Henry started off as back-up musician and would take photographs of the crew and bandmates while on tour… as a hobby. And it wasn’t until a certain recording artist was impressed enough with his pictures that Henry gave in to his identity as a professional photographer. Danny: “And he’s fabulous. He’s great. Well, he’s a wonderful photographer. What a good story!”

“… did he start by wanting to be a photographer when he was eleven? I mean, do you go from wanting to be a fireman to being a photographer? Maybe? Especially now. Because while you’re on the phone in between texting you can take pictures but they suck. And now everybody puts eight hundred pictures on Facebook.”

But Danny maintains he has been and always will be an amateur photographer. “I think of Guy Webster’s photographs which to me were the definition of Los Angeles music in the 60s. When I brought Nico to Elektra… one of the things I’m proudest of… I said ‘Guy Webster’s gotta’ do this shoot.’ The art director at Elektra and I hated each other. But with Guy Webster I knew it wouldn’t get personal because of his greatness. But I don’t know how he got started… did he start by wanting to be a photographer when he was eleven? I mean, do you go from wanting to be a fireman to being a photographer? Maybe? Especially now. Because while you’re on the phone in between texting you can take pictures but they suck. And now everybody puts eight hundred pictures on Facebook.”

But Danny’s passion for photography hasn’t lessened all too much due to the current trend of Snapchat and Instagram celebrity wannabes, “I’m like a kid when I look at a camera in a store. I look through a window and go ‘ooh! ahhh!’ But I like to keep it simple with my little 330. I have a picture in the Times today of Duncan Hannah. From 1973. It’s being used to promote his story. My photograph of Duncan is the one being used to illustrate this story of Duncan Hannah! Does that make me a professional? But I am in the Times. Hey, that’s good, I guess.”

Danny Fields may have to prepare himself for a new kind of fame thanks to this year’s documentary “Danny Says.”Directed by Brendan Toller, it has been making the festival rounds and gaining a lot of positive reviews (J Hurtado of Twitchfilm.com says of the doc, “more than just a remarkable story, it’s a wonderfully ebullient film”). I ask Danny if there is credence to the rumors that the “Danny” in the Ramones song title is actually “Danny Fields?” “It was originally called ‘Tommy Says’ because Tommy was acting as their manager. But the song is not about me,” he confirms. “It’s about Joey’s love for his girlfriend and how he misses her. But it does happen to have my name in the title. It is a beautiful song. And a Phil Specter production… it should have been a hit.”

I then ask him if he’s happy with the documentary.

Danny: “I saw it once in order to know if I would be unhappy with it. That mattered to me. Or that I’d have to kill myself or something. And I had not seen a minute of the footage yet. Brendan was in my life! He was ripping through my closets and my memorabilia and my photographs and calling my friends and interviewing. I never said how’s it going or what’s happening. I never wanted it to be seen as a vanity movie. You know, commissioned by me. I saw it once and I thought Brendan has done a really good job. It’s entertaining.”

Me: “yes, it’s not your movie but you are the subject. A lot of the attention surrounding this film will be about your association with this movie—“

Danny: “yeah, I know, I know. And I’m happy that’s what it is. I’m most pleased with the job Brendan has done. But it’s not my movie. Is it about me? Yeah. I have one of my best and oldest friends… we were having dinner… he refused to be in it. And I said ‘oh my god, tell me why?’ And he said, ‘because you can’t be real! You can only say nice things! And I know you through your f—k ups and successes. And you can’t talk about your f—k ups, it’s a movie. It’s like a memorial or a dinner in you honor. It’s not a roast. It’s a toast.’ So I said “thank you for saying that.’ But there are enough wonderful people in the movie: Iggy Pop, Leee Childers, Tommy Ramone… Man, many of them are dead now. Too many.”

As for now, Danny is looking forward to this trip to London to discuss his involvement with the “inception of Punk” and to promote “My Ramones.” It is an opportunity that allows him to present himself as a photographer again. “That makes it a special time for me. More than it being the 40th anniversary. That’s me taking some photographs that I think are worthy of being shared and worthy of those guys who are all gone now. Yeah, it’s about them.”

“My Ramones” will be available as both a standard and deluxe addition and can be pre-ordered on First Third Books website. “Danny Says,” the documentary on Danny Fields, will be distributed by Magnolia Pictures sometime this year.